Futures, representing an asynchronous computation task, are the basis for implementing asynchronous tasks in Rust. Unlike other languages, the computation does not automatically execute in the background, it needs to actively call its poll method. Tokio is the most widely used asynchronous runtime in the community. It uses various tips internally to ensure that Futures are scheduled and executed fairly and timely. However, since the execution of a Future is cooperative, starvation can inevitably occur in some scenarios.

This article will analyze a problem I encountered while developing CeresDB and discuss issues that may arise with Tokio scheduling. Please point out any inadequacies as my knowledge is limited.

Background

CeresDB is a high-performance time series database designed for cloud-native. The storage engine uses an LSM-like architecture where data is first written to memtable, and when some threshold is reached, it is flushed to the underlying storage(e.g. S3). To prevent too many small files, there is also a background thread that does compaction.

In production, I found a strange problem. Whenever compaction requests increased for a table, the flush time would spike even though flush and compaction run in different thread pools and have no direct relationship. Why did they affect each other?

Analysis

To investigate the root cause, we need to understand Tokio’s task scheduling mechanism. Tokio is an event-driven, non-blocking I/O platform for writing asynchronous applications, users submit tasks via spawn, then Tokio’s scheduler decides how to execute them, most of time using a multi-threaded scheduler.

Multi-threaded scheduler dispatches tasks to a fixed thread pool, each worker thread has a local run queue to save pending tasks. When starts, each worker thread will enter a loop to sequentially fetch and execute tasks in its run queue. Without a strategy, this scheduling can easily become imbalanced. Tokio uses work stealing to address this - when a worker’s run queue is empty, it tries to “steal” tasks from other workers’ queues to execute.

In the above, a task is the minimum scheduling unit, corresponding to await in our code. Tokio can only reschedule on reaching an await, since future execution is a state machine like below:

async move { fut_one.await; fut_two.await; }

This async block is transformed to something below when get executed:

// The `Future` type generated by our `async { ... }` block struct AsyncFuture { fut_one: FutOne, fut_two: FutTwo, state: State, } // List of states our `async` block can be in enum State { AwaitingFutOne, AwaitingFutTwo, Done, } impl Future for AsyncFuture { type Output = (); fn poll(mut self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<()> { loop { match self.state { State::AwaitingFutOne => match self.fut_one.poll(..) { Poll::Ready(()) => self.state = State::AwaitingFutTwo, Poll::Pending => return Poll::Pending, } State::AwaitingFutTwo => match self.fut_two.poll(..) { Poll::Ready(()) => self.state = State::Done, Poll::Pending => return Poll::Pending, } State::Done => return Poll::Ready(()), } } } }

When we call AsyncFuture.await, AsyncFuture::poll get executed. We can see that control flow returns to the worker thread only on state transitions (Pending or Ready). If fut_one.poll() contains blocking API, the worker thread will be stuck on that task. Tasks on that worker’s run queue are likely to not be scheduled timely despite work stealing. Let me explain this in more details:

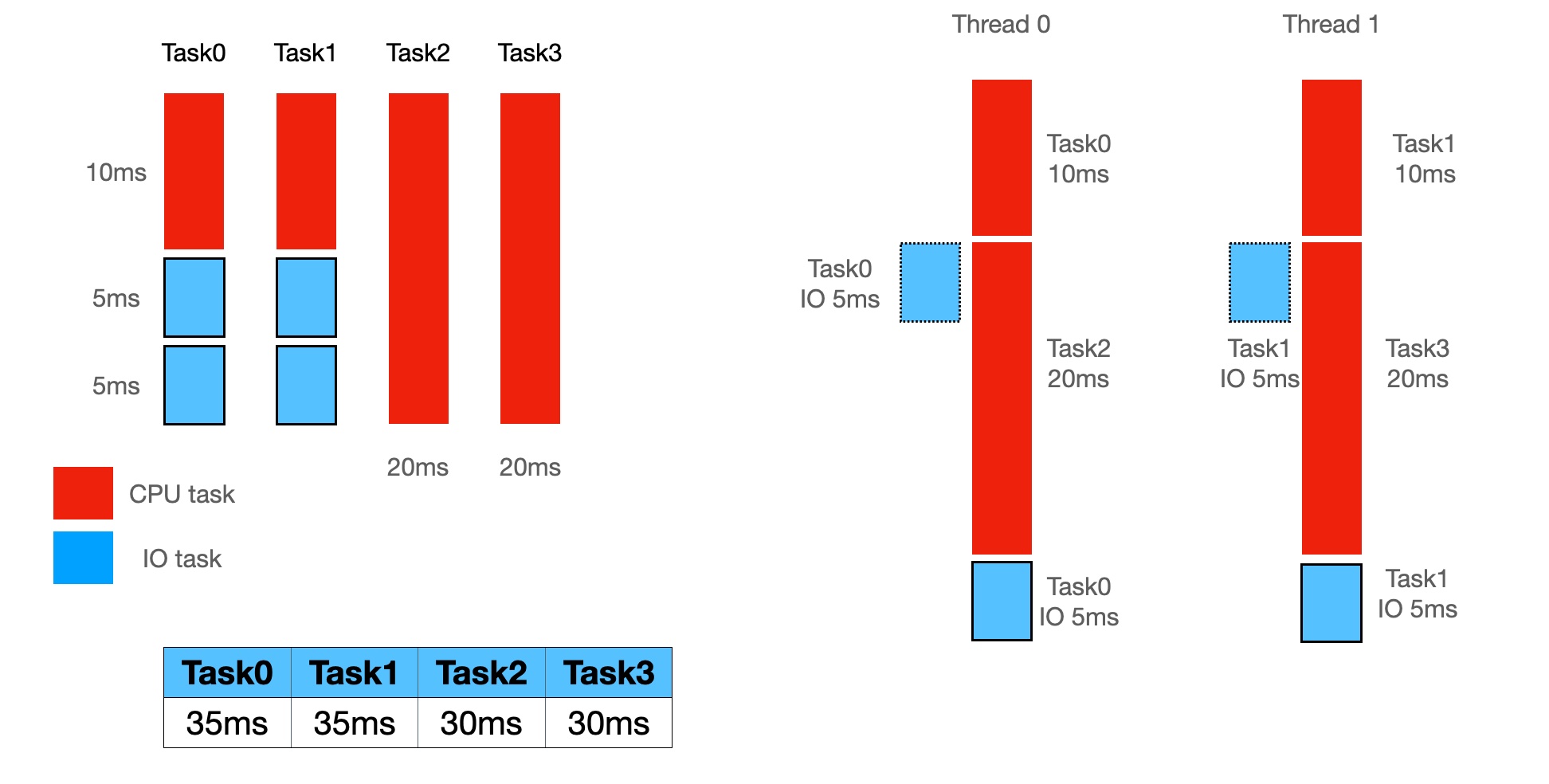

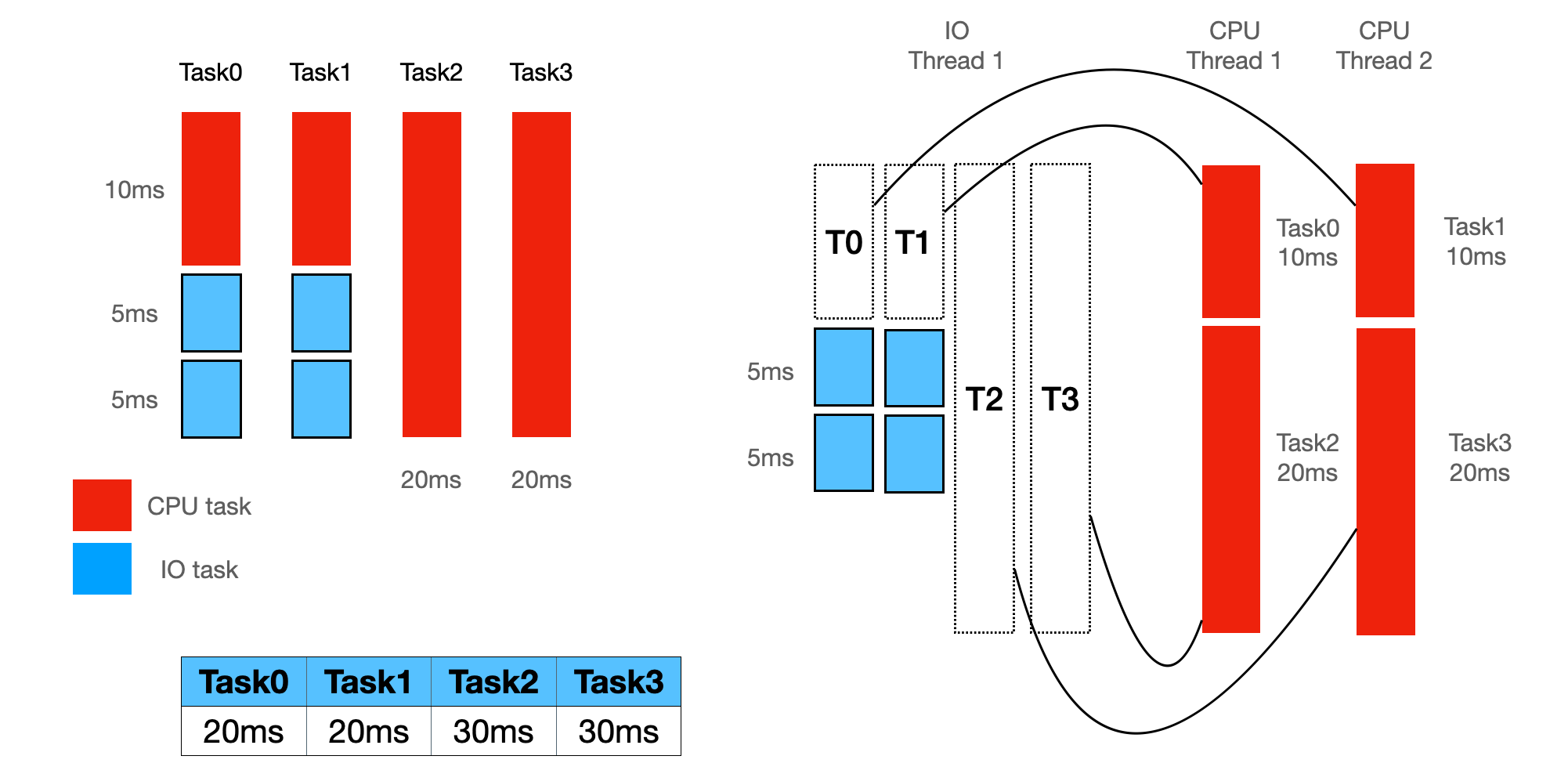

In the above figure, there are four tasks:

- Task0, Task1 are hybrid, which contain both IO and CPU work

- Task2 and Task3 are purely CPU-bound tasks

The different execution strategy will lead to different time consumptions of the tasks.

- In Figure 1, CPU and IO tasks are mixed in one thread, Task0 and Task1 will take 35ms in the worst case.

- In Figure 2, CPU and IO tasks are separated and executed in two runtimes, in this case, Task0 and Task1 both take 20ms.

Therefore, it is generally recommended to use spawn_blocking to execute tasks that may take a long time to execute in Tokio, so that the worker thread can gain control as quickly as possible.

With the above knowledge in mind, let’s try to analyze the question posed at the beginning of this article. The specifics of the flush and merge operations can be expressed in the following pseudo-code:

async fn flush() { let input = memtable.scan(); let processed = expensive_cpu_task(); write_to_s3(processed).await; } async fn compact() { let input = read_from_s3().await; let processed = expensive_cpu_task(input); write_to_s3(processed).await; } runtime1.block_on(flush); runtime2.block_on(compact);

As we can see, both flush and compact have the above issue - expensive_cpu_task can block the worker thread, affecting s3 read/write times. The s3 client uses object_store which uses reqwest for HTTP.

If flush and compact run in the same runtime, there is no further explanation needed. But how do they affect each other when running in different runtimes? I wrote a minimal program to reproduce this.

This program has two runtimes, one for IO and one for CPU scenarios. All requests should take only 50ms but actual time is longer due to blocking API used in the CPU scenario. IO has no blocking so should cost around 50ms, but some tasks, especially io-5 and io-6, their cost are roughly 1s:

[2023-08-06T02:58:49.679Z INFO foo] io-5 begin [2023-08-06T02:58:49.871Z TRACE reqwest::connect::verbose] 93ec0822 write (vectored): b"GET /io-5 HTTP/1.1\r\naccept: */*\r\nhost: 127.0.0.1:8080\r\n\r\n" [2023-08-06T02:58:50.694Z TRACE reqwest::connect::verbose] 93ec0822 read: b"HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\nDate: Sun, 06 Aug 2023 02:58:49 GMT\r\nContent-Length: 14\r\nContent-Type: text/plain; charset=utf-8\r\n\r\nHello, \"/io-5\"" [2023-08-06T02:58:50.694Z INFO foo] io-5 cost:1.015695346s

The above log shows io-5 already took 192ms before the HTTP request, and cost 823ms from request to response, which should only be 50ms. It seems like the connection pool in reqwest have some weird issues, that’s the IO thread is waiting for connections held by the CPU thread, increasing cost of IO task. Setting pool_max_idle_per_host to 0 to disable connection reuse solve the problem.

I filed this issue here, but haven’t get any answers yet, so the root cause here is still unclear. However I gain better understand how Tokio schedule tasks, it’s kind of like Node.js, we should never block schedule thread. In CeresDB we fix it by adding a dedicated runtime to isolate CPU and IO tasks instead of disabling the pool, see here if curious.

Summary

Through a CeresDB production issue, this post explains Tokio scheduling in simple terms. Real situations are of course more complex, users need to analyze carefully how async code gets scheduled before finding a solution. Also, Tokio makes many detailed optimizations for lowest possible latency, interested readers can learn more from links below:

- Making the Tokio scheduler 10x faster

- One bad task can halt all executor progress forever #4730

- Using Rustlang’s Async Tokio Runtime for CPU-Bound Tasks

Finally, I hope readers can realize potential issues when using Tokio. As a rule of thumb, try to isolate blocking tasks to minimize impact on IO tasks.