Whenever we discuss “unsafe” in Rust, the concept of “invariant” is never far behind. In the context of Rust, it generally refers to the properties that need to be upheld. For instance:

- Given a

x: bool, there is an invariant:xcan only betrueorfalse. - Given a

p: Pin<Box<T>>, one of the invariants is that the memory pointed to bypwill not move (whereT: !Unpin). unsafe fn read<T>(src: *const T) -> T, one of the invariants here is thatsrcpoints to a fully initialized value.

Rust contains various types of invariants, with most of them being upheld by the type checker, while some require manual verification to ensure.

Classification of Invariants

We can roughly categorize the invariants in Rust into two types: language-level invariants and library-level invariants.

Language-level invariants

Language-level invariants, also known as validity, play a crucial role in Rust. These invariants guide the compiler to generate correct code and optimize it effectively. One typical example of optimization using invariants is niche optimization. For instance, the size of Option<&T> is optimized to be the size of a pointer. This optimization relies on the invariant that &T is non-null. This allows representing None using a null value, thus compressing the type’s size. It’s worth noting that additional optimizations can be performed here. When T doesn’t contain UnsafeCell, an invariant of &T is that the value it points to is immutable. Therefore, we can inform LLVM that the &T pointer is readonly, enabling LLVM to optimize based on this information.

However, violating language-level invariants leads to fatal consequences known as Undefined Behavior (UB). The compiler no longer guarantees any behavior of the program (or even that the output will be an executable file). For example, as mentioned earlier, forcibly casting values other than true and false, like 2, to a bool will result in undefined behavior. Similarly, reading an uninitialized value also constitutes undefined behavior. Here is a list of some clearly defined instances of UB. Violating language invariants can lead to these UB scenarios (but not limited to this list). These invariants are mandatory to adhere to.

However, due to compiler errors, there can also be instances where these invariants are unintentionally violated, causing the failure of business logic that depends on them. This falls into the category of compiler bugs.

Library-level invariants

Library/Interface-level invariants, also known as safety, are usually defined by the authors of libraries. For example, specifying an invariant that values of the struct Even(u64) must be even numbers allows the use of this property directly in business logic.

For the author of Even, they can provide an interface like this (assuming this library only offers these few interfaces):

impl Even { /// Returns Some when n is even /// Returns None when n is not even pub fn new(n: u64) -> Option<Self> { if n % 2 == 0 { Some(Self(n)) } else { None } } /// n must be even pub fn unchecked_new(n: u64) -> Self { Self(n) } /// Returns a value that is even pub fn as_u64(&self) -> &u64 { &self.0 } }

For the interface Even::new, the invariant is guaranteed by the author of Even; for Even::unchecked_new, the invariant is guaranteed by the caller. Compared to language-level invariants, this invariant is much more “gentle” - breaking this invariant will not necessarily result in UB within this library (but still lead to unexpected behavior in the program).

The invariant of Pin is also a very typical library-level invariant. Generally, the “non-movable” invariant of Pin<P> is guaranteed by the author of Pin<P>. For example, all the interfaces provided by Pin<Box<T>> prevent moving the value it points to, and users don’t need to worry about accidentally breaking this invariant with incorrect operations (assuming it’s within safe Rust and guaranteed by the type system). However, breaking the Pin invariant might not immediately result in UB; instead, UB might occur in subsequent usage (e.g., accessing memory that a reference within a self-referential structure still points to after the structure has been moved).

In Rust, the majority of invariants are library/interface-level invariants. Examples include “a str must be encoded in UTF-8,” “Send and Sync” constraints, and various IO-safety properties introduced later on, all falling under this category of invariants.

Typed Proofs of Invariants

Humans are prone to making mistakes, and we can’t rely solely on humans to ensure that invariants aren’t violated. So, do we have a solution for automatically checking whether invariants are violated? Yes, Rust provides a powerful type system that can enforce various kinds of invariants based on its type rules.

For example, according to the borrowing rules of the type system, the scope of a reference’s borrowing must be within the scope of the original value. This ensures that &T references are always valid:

let p: &String; { let s = String::from("123"); p = &s; } // Compilation error because the lifetime of `p` outlives the scope of `s` println!("{p:?}");

During compilation, type checks are performed, and when code doesn’t satisfy the type rules, the compiler treats it as an illegal program and disallows compilation. Using type rules to ensure various invariants in programs is the part of Rust that is known as “safe Rust.”

Rust adheres to a crucial principle: Under safe Rust, the invariants of all publicly exposed interfaces in a library are not violated. This principle is known as soundness. For instance, the earlier example of Even is not sound because it provides the Even::unchecked_new interface, which can break the invariant of Even under type checking. However, without providing this interface, the library becomes sound, as you cannot construct a non-even Even value due to the support of the type system, thereby maintaining the invariant.

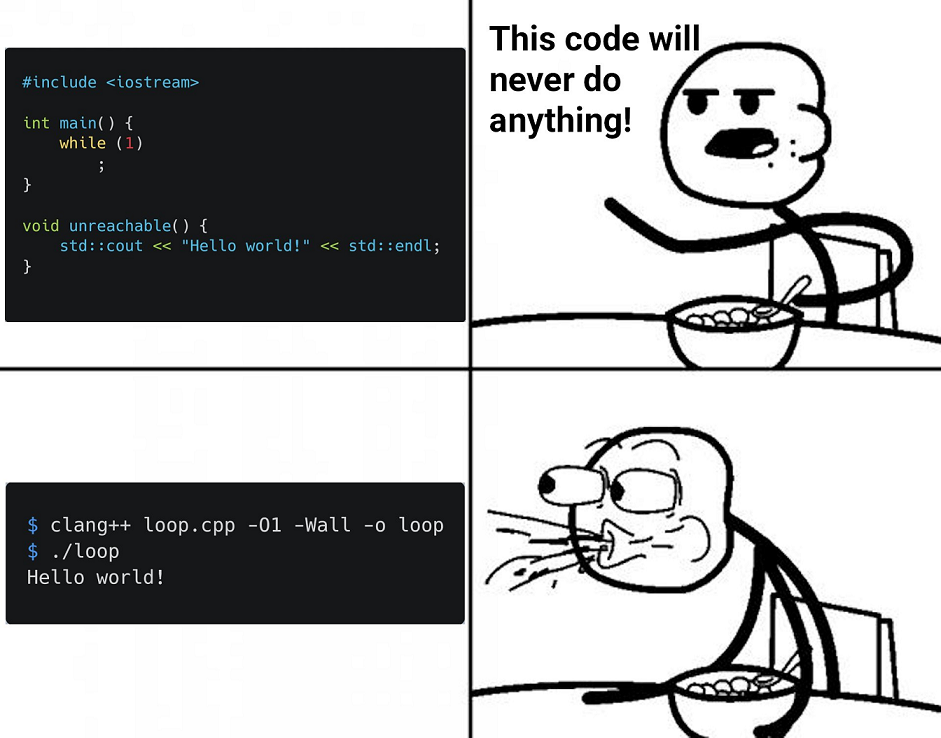

Of course, some libraries strictly adhere to this principle, like the standard library. In fact, if we use only the std library, we can go a step further and say that under safe Rust, Undefined Behavior (UB) won’t occur. Many languages have type systems, but not all of them offer such strong guarantees. For instance, in C++, a small mistake like writing an infinite loop can result in UB.

Moreover, invariants are not just the responsibility of the programmer; they are a collective effort that all parties must strive to uphold. Whoever violates an invariant is at fault, and it’s crucial to determine who bears the responsibility. Rust’s module system, also known as crates, plays a crucial role in this regard by preventing external parties from undermining the invariants guaranteed within a library.

This rule is known as the coherence rules, which forbid implementing third-party traits for third-party types. For example, let’s consider a library that implements a pointer type Ptr<T> with the following methods:

impl Deref for Ptr<T> { type Target = T; // ... } impl<T> Ptr<T> { // Since `DerefMut` is not implemented, `Pin<Ptr<T>>` has no method to move `T` pub fn pin(t: T) -> Pin<Ptr<T>> { ... } pub fn new(t: T) -> Ptr<T> { ... } // Can access `&mut T` before being `Pin`ned pub fn borrow_mut(&mut self) -> &mut T { ... } }

Without coherence rules, we could implement DerefMut for Ptr and break the invariant of Pin (which was initially guaranteed within the library):

impl DerefMut for Ptr<Unmovable> { fn deref_mut(&mut self) -> &mut Unmovable { let mut tmp = Box::new(Unmovable); // Moved Unmovable out swap(self.borrow_mut(), &mut tmp); Box::leak(tmp) } } let unmovable = Unmovable::new(); let mut ptr: Pin<Ptr<Unmovable>> = Ptr::pin(unmovable); // Calling Pin::as_mut() invokes Ptr::deref_mut(), moving unmovable // Breaking the `Pin` invariant, unsoundness! // This vulnerability could lead to UB. ptr.as_mut();

In fact, a similar issue with Pin once occurred in the standard library… (&T, &mut T, Box<T>, Pin<P> can all violate coherence rules, enabling the creation of such vulnerabilities, but this has been addressed in subsequent fixes NOT YET).

Due to the coherence rules, you cannot do this anymore. If your invariant is guaranteed locally, third parties cannot undermine it. As a result, in Rust, responsibility can be strictly divided: if a bug arises from normal usage, it’s the library author’s fault, as normal usage should not be able to break the library’s internal invariants.

(However, I’m curious about how languages like Haskell and Swift, which allow implementing third-party type classes or protocols for third-party libraries, ensure that their libraries aren’t affected by downstream or other third-party libraries.)

Relationship between Invariants and unsafe

However, Rust’s type system is not all-powerful. There are some invariants that cannot be proven by the type system, and this includes certain forms of validity (language-level invariants). These invariants need to be guaranteed by the programmers themselves. While other invariant violations might lead to minor consequences, validity issues are much more critical; they can cause catastrophic failures. To address these situations, Rust introduced the unsafe keyword to deal with matters related to validity.

unsafe fn: Indicates that an interface has certain invariants that, if not upheld by the caller, might break validity and result in Undefined Behavior (UB). These invariants can be treated as axioms directly used in the implementation of the interface.unsafe {}: Asserts that the internal invariants have been adhered to. Rust completely trusts the promises made by the programmer.unsafe trait/unsafe implare similar.

Thus, Rust is divided into two parts by unsafe: safe Rust, where the type system proves guarantees (and compiler takes responsibility for any issues), and unsafe Rust, where programmers need to prove safety themselves (and they take responsibility for any issues).

Determining which interfaces (fn and trait) should be marked as unsafe is quite restrained in Rust; not all invariants that the type system cannot prove should be marked as such. Only invariants related to validity and FFI should be marked as unsafe, and marking them should be done sparingly. For instance, UnwindSafe is not marked as unsafe because within the standard library, nothing can cause UB due to lack of unwinding, and when using the standard library without any unsafe constructs, UB does not arise.

FFI is a peculiar case. It differs from validity in that its correctness cannot be ensured by Rust’s compiler because Rust lacks information about the other side of the FFI boundary. However, the other side of FFI can do anything, so theoretically, performing FFI is never safe. In such cases, programmers must understand the consequences of FFI, and unsafe { call_ffi() } implies, “I am aware of the consequences of invoking FFI and am willing to accept all the impacts it brings.”

Apart from what should be marked as unsafe, strict review of the contents of unsafe is also essential.

Firstly, check the invariants corresponding to unsafe on the interfaces. For instance, are the invariants sufficient (do they guarantee safety)? Are there any conflicting invariants (e.g., x: u64 but also requiring x < 0, which cannot be achieved)?

Then, rigorously verify if the conditions within unsafe {}/unsafe impl are met. Some things cannot be relied upon, those invariants that haven’t been proven and aren’t marked as unsafe, such as:

- The previous example of

Even, which claims to represent even numbers - What an unknown

T: UnwindSafe“claims” about being unwindsafe - What an unknown

T: Ord“claims” about total ordering

These can all be violated under safe conditions, but we can’t hold anyone accountable under safe conditions. (Again, I feel that these should be called hints rather than invariants, as nobody is responsible for them; just like the earlier definition of Even.)

A general rule for safe usage is to rely on:

- Properties of concrete types. For example,

u64: Ordensures total ordering, which you can guarantee. Here, concrete types act as a white box, and you know all their properties. - Invariants declared through

unsafe.

Humans are fallible. So, how can we check if we violate validity? There are tools available, although they are limited. Currently, you can use MIRI (a Rust interpreter, essentially representing standard Rust behavior) to run your Rust programs (limited to pure Rust code). MIRI maintains the state of all correct Rust behaviors. When your program triggers UB, MIRI reports an error. However, there are limitations; MIRI can only tell you that UB occurred, not which invariant was violated to cause the UB. Moreover, MIRI cannot exhaustively cover all scenarios, and even if it does, it cannot prove that the provided interfaces are sound. (Similar to testing.)

There are also some limited formal verification tools available, such as flux, but I won’t delve into that here.

unsafe is a distinctive feature of Rust. Without unsafe, achieving complete safety leads to these scenarios:

- All validity could be proven using types - requiring an incredibly powerful type system (even for simple tasks), leading to an overly complex type system with heavy cognitive load for users and challenges in proving the reliability of the type system. Additionally, it might hit theoretical limits where some things are undecidable.

- All validity could be checked dynamically at runtime, or UB could be eliminated at runtime - introducing inevitable overhead in various places, making it hard to achieve optimal performance. It might even limit users from performing low-level operations, requiring explicit checks every time (similar to Haskell’s inability to define arrays using the language’s own syntax, relying on runtime or FFI).

A Few More Points to Add

- Rust’s type system has not yet been proven to be entirely reliable. This implies that there might be inconsistencies and contradictions in certain rules. Consequently, at this stage, proofs of invariants might not always be dependable.

- The soundness of Rust’s standard library has also not been fully established. This means that certain interface invariants within the standard library might still be susceptible to violation.

- The vast majority of third-party libraries in Rust have not been verified for soundness, especially those that internally employ

unsafeconstructs. - Rust’s compiler is also capable of inadvertently breaking invariants through incorrect optimizations, potentially allowing us to create a Segmentation fault in safe Rust.

- The platform on which a Rust program runs can also undermine invariants. For example,

proc/self/memcan disrupt memory-exclusive invariants by altering memory. However, from a practical standpoint, Rust accommodates such corner cases.

In the future, points 1 and 2 might see resolution, but 3, 4, and 5 appear to be inevitable challenges. This indicates that Rust’s safety has limitations; critical aspects still rely on human judgment, although humans remain fallible. This reminds me of Linus Torvalds’ quote about safety:

So?

You had a bug. Shit happens.“

However, even with that said, Rust’s emphasis on safety still holds statistical significance in its favor. Moreover, the clear allocation of responsibility when problems arise adds meaningful accountability to the equation.