Write a SQL Optimizer using Egg

The SQL optimizer is an important module in relational database systems. Its purpose is to optimize SQL statements to improve query efficiency. To help beginners understand the basic principles of the SQL optimizer, we have implemented a small SQL optimizer using the Egg framework in Rust language. Although its code is less than a thousand lines, it covers classic optimization techniques such as expression simplification, constant folding, predicate pushdown, column pruning, join reordering, and cost estimation. It includes both rule-based optimization (RBO) and cost-based optimization (CBO), and it is capable of working on actual TPC-H queries.

In this article, we will briefly introduce the implementation process of this project. You can find the relevant code in the SQL Optimizer Labs, or learn about its application in the RisingLight project.

The Egg Library

Egg is a program optimizer framework written in Rust. Its core technology is based on a method called Equality Saturation. The idea behind it is to gradually rewrite expressions to find all equivalent forms and then identify the optimal solution among them. During this process, Egg uses the e-graph data structure to efficiently query and maintain equivalence classes at runtime, reducing the time and space costs of program optimization.

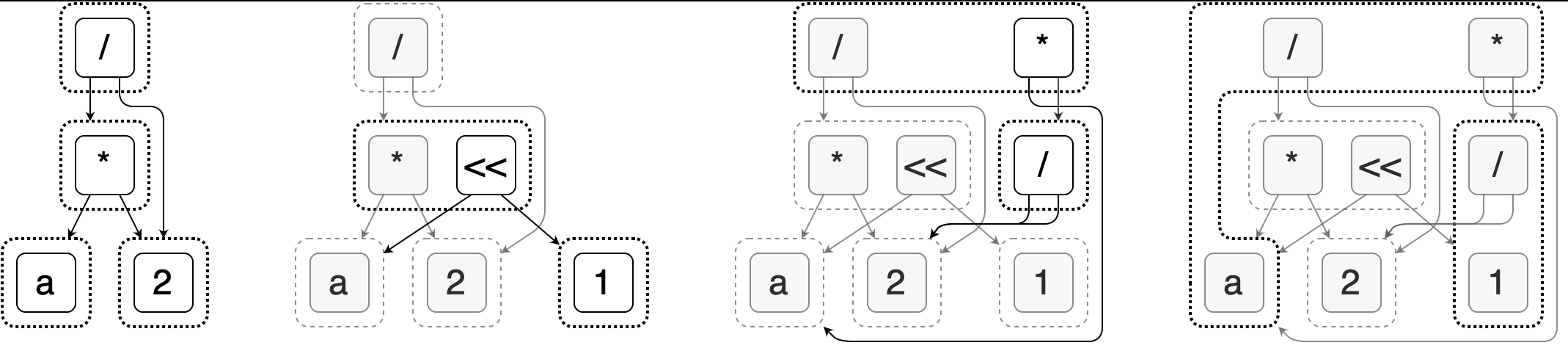

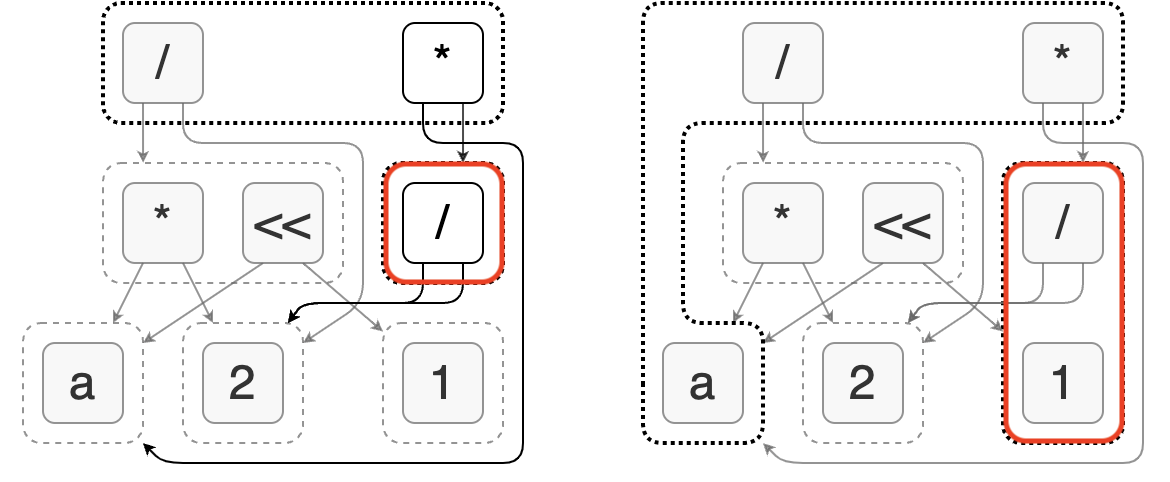

The following image, taken from the Egg official website, shows the step-by-step process of optimizing the expression a * 2 / 2 to simply a.

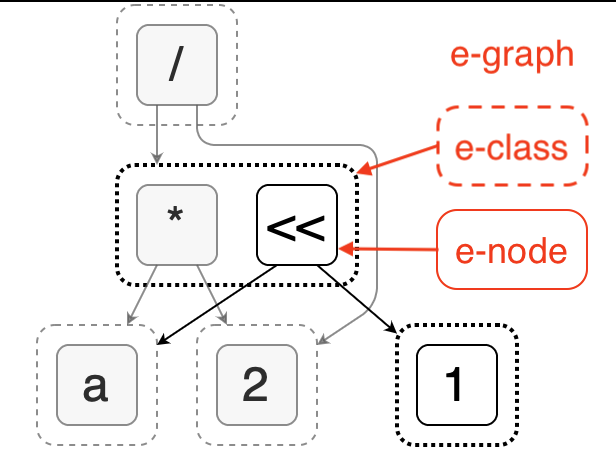

Taking the second image as an example, we can see that it consists of three layers of structure: e-graph, e-class, and e-node.

Each node in the diagram is an e-node, which can represent a variable, a constant, or an operation. Multiple e-nodes can form an e-class, which represents a group of equivalent nodes with the same semantics that can be replaced by each other. The child nodes of each e-node are e-classes, which together form an e-graph. Therefore, this data structure can represent a large number of possible combinations with compact space.

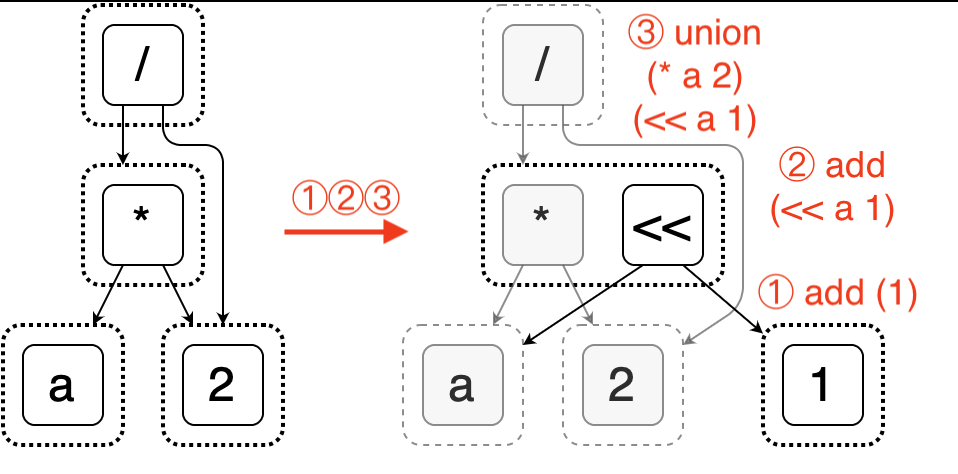

The e-graph also allows for dynamic insertion of e-nodes and merging of e-classes, which enables expression rewriting. The following diagram illustrates the process of inserting a new expression a << 1 into the graph and merging it with a * 2.

Egg supports user-defined rules using S-expressions. For example, the rule shown in the above figure can be expressed as (* ?a 2) => (<< ?a 1). More complex rules can also be written in Rust if needed. This makes Egg highly flexible and extensible. Developers can quickly implement an optimizer for their own language based on Egg. The following sections of this article demonstrate its application in SQL.

Lastly, it’s worth mentioning that the academic paper behind Egg has won the Distinguished Paper Award at POPL 2021. If you are interested, you can find more resources on their website.

Define The SQL Language

The first step to using Egg is to define the language, which in this case is SQL statements and their expressions.

Egg fully utilizes algebraic data types (ADT) in Rust to define the language. We can define an enum using the define_language macro provided by Egg to describe a node.

define_language! { pub enum Expr { // values Constant(DataValue), // null, true, 1, 1.0, "hello", ... Column(ColumnRefId), // $1.2, $2.1, ... // list "list" = List(Box<[Id]>) // (list ...) // operations "+" = Add([Id; 2]), // (+ a b) "and" = And([Id; 2]), // (and a b) // plans "scan" = Scan([Id; 2]), // (scan table [column..]) "proj" = Proj([Id; 2]), // (proj [expr..] child) "filter" = Filter([Id; 2]), // (filter condition child) "join" = Join([Id; 4]), // (join type condition left right) "hashjoin" = HashJoin([Id; 5]), // (hashjoin type [left_expr..] [right_expr..] left right) "agg" = Agg([Id; 3]), // (agg aggs=[expr..] group_keys=[expr..] child) "order" = Order([Id; 2]), // (order [order_key..] child) "asc" = Asc(Id), // (asc key) "desc" = Desc(Id), // (desc key) "limit" = Limit([Id; 3]), // (limit limit offset child) } }

The above code is a simplified version that includes four types of nodes: value, list, operator, and plan node.

- Value: the leaf node in an expression. It can be a

Constant, or a variableColumnthat refers to a column in a table. - List: this is a special node that we introduce, representing an ordered list of several elements. It can have any number of child nodes. Note that from here on, each variant is prefixed with a string literal. It is used to identify this node in S-expressions. The specific representation is shown in the comment.

- Operator: usually a middle node in an expression. Its associated Rust type can be either

Id,[Id; N], orBox<[Id]>, which respectively represent 1, N, or an indefinite number of child nodes. - Plan Node: similar to an operator, but it operates on a table instead of a value. A SQL statement is transformed into a query plan tree composed of several nodes. Each plan node contains not only child nodes (

child,left,right) which are plans, but also several parameters composed of expressions.

Let’s say we have a SQL statement like this:

SELECT users.name, count(commits.id) FROM users, repos, commits WHERE users.id = commits.user_id AND repos.id = commits.repo_id AND repos.name = 'RisingLight' AND commits.time BETWEEN date '2022-01-01' AND date '2022-12-31' GROUP BY users.name HAVING count(commits.id) >= 10 ORDER BY count(commits.id) DESC LIMIT 10

Its query plan can be represented in our language as follows:

(proj (list $1.2 (count $3.1)) (limit 10 0 (order (list (desc (count $3.1))) (filter (>= (count $3.1) 10) (agg (list (count $3.1)) (list $1.2) (filter (and (and (and (= $1.1 $3.2) (= $2.1 $3.3)) (= $2.2 'RisingLight')) (and (>= $3.4 '2022-01-01') (<= $3.4 '2022-12-31'))) (join inner true (join inner true (scan $1 (list $1.1 $1.2 $1.3)) (scan $2 (list $2.1 $2.2 $2.3))) (scan $3 (list $3.1 $3.2 $3.3 $3.4 $3.5)) )))))))

The next step is to define a series of rules to perform equivalent transformations on the expression above, and eventually find the representation with the smallest cost as the optimized result.

Define Rewrite Rules

In this section, we will use the API provided by Egg to describe optimization rules. Due to space limitations, we will choose several representative ones for a brief introduction. They are:

- Expression simplification

- Constant folding

- Predicate pushdown

- HashJoin

- Join reordering

- Cost function

Expression Simplification

Firstly, we simplify expressions in the plan nodes.

For example, the multiplication-to-shift rule mentioned at the beginning can be described in Egg using the rewrite macro as follows:

rewrite!("mul2-to-shl1"; "(* ?a 2)" => "(<< ?a 1)")

The strings on either side of => represent the expression patterns before and after the transformation, where ?a represents a variable that can be replaced with any expression. When the runner finds an expression that matches this pattern, it generates a new expression according to the pattern on the right and unions it with the original node to form an equivalence class. By the way, => can also be replaced with <=> to indicate a bidirectional transformation.

Some rules require certain conditions to be met before execution. For example, the following rule is only valid when the divisor is not zero:

rewrite!("div-self"; "(/ ?a ?a)" => "1" if is_not_zero("?a"))

Here we use the is_not_zero function to determine whether the variable ?a is not zero. However, how do we know whether an expression is non-zero? This is where analysis comes in.

Constant Folding

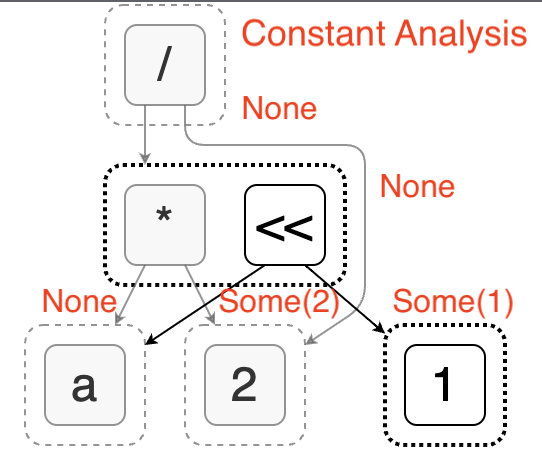

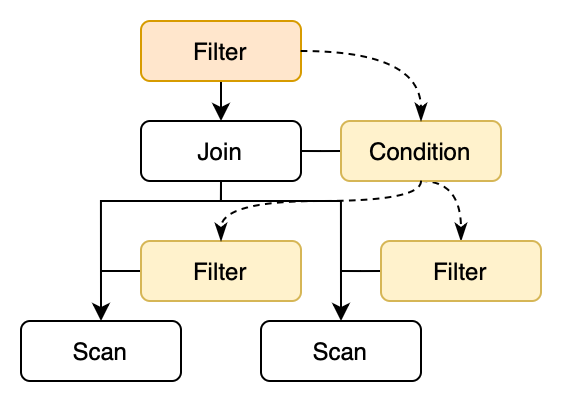

Egg’s analysis allows us to associate arbitrary value with each e-class to describe its characteristics, such as whether it is a constant, what data type it is, or which columns are referenced. To solve the problem mentioned above, we can introduce constant analysis. It determines whether an expression is a constant and, if so, provides the specific constant value. The following figure shows the constant analysis results for an expression.

During the process of analysis, Egg allows us to modify the e-graph by adding e-nodes or merging e-classes. By using this mechanism, we can implement constant folding optimization: replacing expressions that are known to be constants with a single value.

As shown in the left side of the figure, in constant analysis, we find that the node (/ 2 2) can be evaluated into the constant 1. At this point, we create a new node 1 (which is already present in the graph) and merge it with (/ 2 2). This completes the constant folding. Its characteristic is that it utilizes the side effect of expression analysis instead of being accomplished by rewriting rules.

In terms of code implementation, each analysis needs to implement the Analysis trait. The documentation provides an example of constant folding, explaining the specific steps for implementing analysis. Interested readers can click on the link to learn more about the details.

Predicate Pushdown

After simplifying the expressions, let’s move on to the SQL plan node. One of the classic optimizations is predicate pushdown.

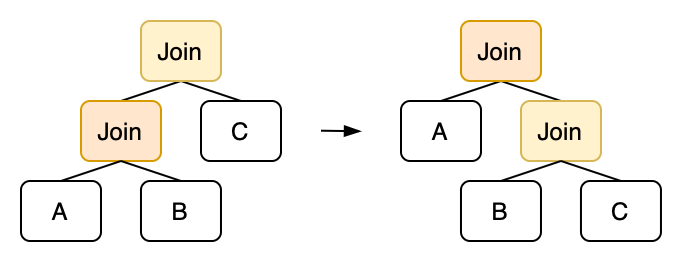

The idea of predicate pushdown is to push the predicates in the Filter node down to the lower-level operators, in order to filter out unnecessary data as early as possible, thereby reducing the amount of data that the upper-level operator needs to process. For example, the following diagram shows the process of pushing the Filter predicates above the Join node down to the Scan nodes. There are mainly two steps:

- Push the Filter predicate down to the Join condition.

- Push the Join condition down to the left and right child nodes, and generate new Filter nodes.

The first step can be described by very simple rules:

rewrite!("pushdown-filter-join"; "(filter ?cond (join inner ?on ?left ?right))" => "(join inner (and ?on ?cond) ?left ?right)" )

However, the second step is quite tricky since there are three possible scenarios:

- ↙️ The predicate only contains columns from the left side and can be pushed down to the left subtree.

- ↘️ The predicate only contains columns from the right side and can be pushed down to the right subtree.

- ⏹️ The predicate contains columns from both sides, making it impossible to push down.

At this point, we need to use the conditional rewrite feature of Egg. Only when the referenced columns in the predicate come from a subtree can we push it down.

rewrite!("pushdown-filter-join-left"; "(join inner (and ?cond1 ?cond2) ?left ?right)" => "(join inner ?cond2 (filter ?cond1 ?left) ?right)" if columns_is_subset("?cond1", "?left") ),

The function columns_is_subset(a, b) here is defined as whether the set of columns used by expression a is a subset of columns provided by plan node b. To achieve this, we need to introduce a new “column analysis”, to calculate the set of columns used and defined by each node. This is somewhat similar to the “use” and “def” sets in live variable analysis. The implementation process is not complicated. You can refer to the code in the RisingLight project for more details.

In addition to pushing down Filter nodes, we can also push down Projection nodes and perform column pruning on the operators along the way. Column pruning can remove unnecessary columns from plan nodes, reducing scan and transmission costs.

HashJoin

The next optimization is to replace the Join operator with a more efficient Hash Join. The basic idea of hash join is to first build a hash table for one side, and then traverse the other side, looking for matching items in the hash table. Its time complexity is O(N + M), which is usually far better than the nested loop join’s O(N * M).

Implementing hash join optimization in Egg is also quite simple. Its main function is to identify the join condition in the form of l1 = r1 AND l2 = r2 AND ..., and then separate the keys on the left and right sides and store them in the HashJoin node. This makes it easy for the executor to directly extract data from the input on both sides in the future.

rewrite!("hash-join-on-one-eq"; "(join ?type (= ?l1 ?r1) ?left ?right)" => "(hashjoin ?type (list ?l1) (list ?r1) ?left ?right)" if columns_is_subset("?l1", "?left") if columns_is_subset("?l2", "?right") ),

For cases where the join condition includes two or more equalities, we can also describe it in a similar way.

Join Reordering

In addition to optimizing join algorithms, we can also adjust the order of multiple joins to minimize the overall execution cost. Different join orders can have vastly different costs.

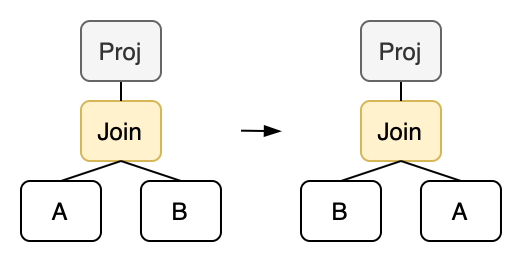

For common inner joins, they satisfy the commutative law and the associative law. From the perspective of the query plan tree, the commutative law is equivalent to swapping the left and right subtrees of a join node, and the associative law is equivalent to performing rotations on the binary tree.

Describing the associative law in Egg is also intuitive:

rewrite!("join-right-rotation"; "(join inner true (join inner true ?left ?mid) ?right)" => "(join inner true ?left (join inner true ?mid ?right))" ),

Note that we have not considered the case where the Join operator has conditions. If the condition of the top-level Join operator contains columns from A, it cannot be moved to the right. If conditions are considered, more complex rules may need to be constructed with column analysis.

Similarly, we can also implement the commutative law:

rewrite!("join-swap"; "(proj ?exprs (join inner ?cond ?left ?right))" => "(proj ?exprs (join inner ?cond ?right ?left))" ),

However, we require that a Projection operator must be placed above the Join in order to perform swapping. Because swapping the left and right subtrees of a Join operator results in a change in the output columns, which does not meet our definition of e-classes. Therefore, we need to apply a Projection on top to ensure that the output of both operators is exactly the same before and after rewriting.

With the above two rules, we can enumerate all possible join orders. For N tables, there are N! different permutations. Which one is the optimal solution? This is where a cost function comes in, which calculates the cost based on the actual sizes of each table.

Cost Function

In the previous optimizations, the rewritten plans are always better than the original ones. These belong to rule-based optimization (RBO). However, join reordering requires an additional cost function to evaluate different plans and choose the one with the minimum cost. This belongs to cost-based optimization (CBO).

Since the equality saturation is naturally based on cost, implementing CBO in Egg is a breeze. We only need to implement the cost function under the CostFunction trait:

pub struct CostFn<'a> { pub egraph: &'a EGraph, } impl egg::CostFunction<Expr> for CostFn<'_> { type Cost = f32; fn cost<C>(&mut self, enode: &Expr, mut costs: C) -> Self::Cost where C: FnMut(Id) -> Self::Cost, { use Expr::*; // Define some helper functions: // rows: estimate the number of rows // cols: return the number of columns // out: amount of data = rows * cols // costs: the total cost of a node match enode { Scan(_) | Values(_) => out(), Order([_, c]) => nlogn(rows(c)) + out() + costs(c), Proj([exprs, c]) | Filter([exprs, c]) => costs(exprs) * rows(c) + out() + costs(c), Agg([exprs, groupby, c]) => (costs(exprs) + costs(groupby)) * rows(c) + out() + costs(c), Limit([_, _, c]) => out() + costs(c), TopN([_, _, _, c]) => (rows(id) + 1.0).log2() * rows(c) + out() + costs(c), Join([_, on, l, r]) => costs(on) * rows(l) * rows(r) + out() + costs(l) + costs(r), HashJoin([_, _, _, l, r]) => (rows(l) + 1.0).log2() * (rows(l) + rows(r)) + out() + costs(l) + costs(r), Insert([_, _, c]) | CopyTo([_, c]) => rows(c) * cols(c) + costs(c), Empty(_) => 0.0, // for other expressions, the cost = 0.1 x AST size _ => enode.fold(0.1, |sum, id| sum + costs(&id)), } } }

This function serves as an example and mainly considers the computational cost of operators and the size of the output data. In actual development, it may be necessary to fine-tune the cost function multiple times until the optimizer can find reasonable results.

After defining the cost function, we can hand it over to Egg to find the optimal expression. Egg provides a Runner to automatically perform this process:

/// Optimize the given plan pub fn optimize(expr: &RecExpr) -> RecExpr { // Do equality saturation based on the optimization rules let runner = egg::Runner::default() .with_expr(&expr) .run(&*rules::ALL_RULES); // Extract the best plan based on the cost function let cost_fn = CostFn { egraph: &runner.egraph, }; let extractor = egg::Extractor::new(&runner.egraph, cost_fn); let (_cost, best_expr) = extractor.find_best(runner.roots[0]); best_expr }

However, the current runner of Egg is not very intelligent. It does not perform heuristic searches based on cost functions when expanding e-classes, but instead expands all possible representations. For more complex queries, such as multi-table joins in TPC-H, it is easy to encounter combinatorial explosion. In addition, some special rewriting rules can be applied infinitely, leading to deep nested expressions, which further exacerbates this phenomenon.

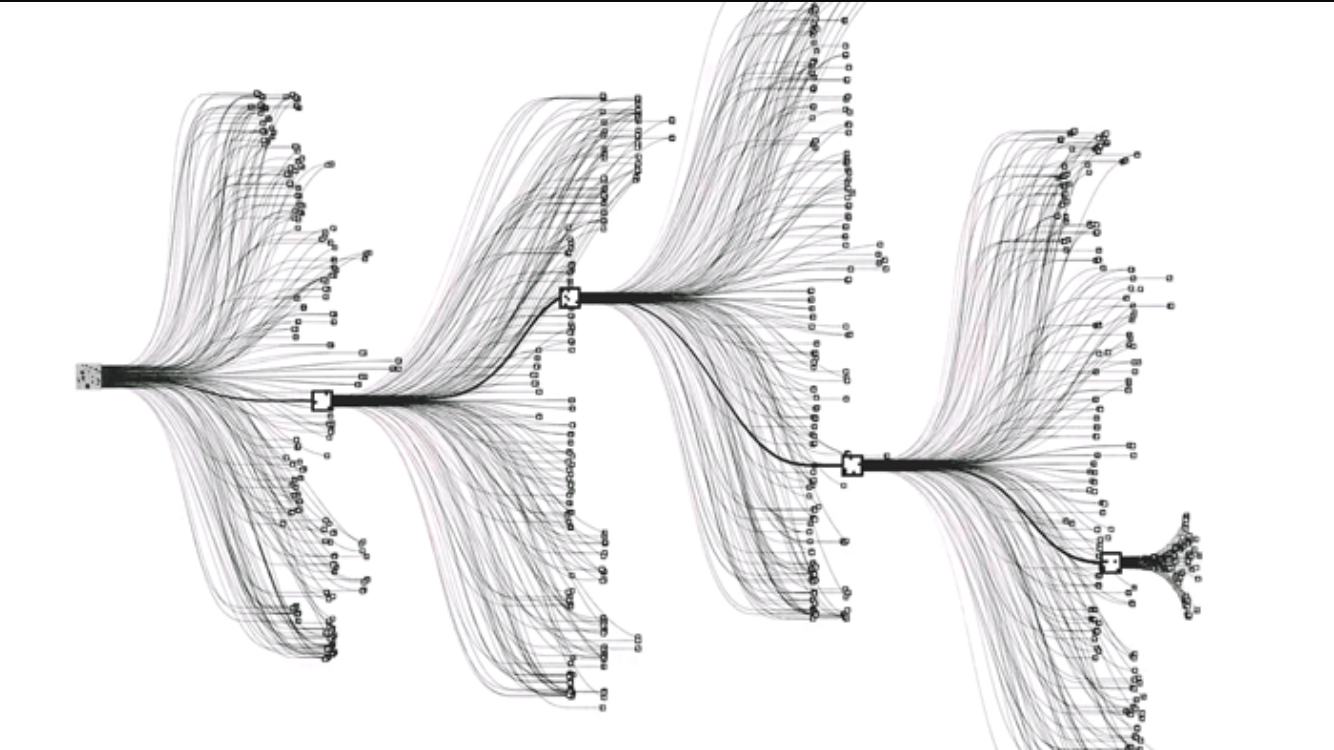

Multi-iteration & multi-stage optimization. Source: AlphaGo.

To avoid this issue, we can manually iterate the above process multiple times, and extract the best plan as the input for the next round of iteration. This can achieve a nearly heuristic search effect. Additionally, we can manually categorize rules into several types for multi-stage optimization, applying only a subset of rules in each stage. With these workarounds, our optimizer can optimize common SQL queries to a satisfactory level in around 100ms. You can see the optimization results of RisingLight on TPC-H queries here.

Conclusion

In this article, we introduced the program optimizer framework Egg and demonstrated how to use it to develop an SQL optimizer.

The core principle of Egg is equality saturation. It rewrites expressions through rules and then finds the optimal solution based on a cost function. When using Egg, developers need to define the language first, then describe the rewrite rules in S-expressions, and finally define the cost function. The rest of the work can be automated by the framework.

Egg is a powerful and user-friendly framework that is ideal for quickly prototyping various optimizers. If you have similar requirements in your work or are interested in writing a database optimizer, you might want to try Egg!