We often require detailed memory statistics per module or query of a large project. Generally, there are two approaches to fine-grained memory statistics:

- Using

allocator_apithroughout, as most of the collections from thestdlibrary in C++ or Rust support it. - For larger blocks (e.g. buffer pools or chunks), manually tracking memory allocation and deallocation.

Both approaches can achieve the goal, but introduce too much complexity to the project.

Meanwhile, in Rust, the allocator_api feature is still unstable. During testing, we found some APIs that could lead to memory leaks and could not be used in production. Thus, we are searching for a fast, stable, and less complex way to maintain statistics.

GlobalAlloc + task_local

GlobalAlloc was introduced in Rust 1.28. It is an abstraction layer that introduces the concept of a global allocator. GlobalAlloc should be thread-safe and can be used for memory statistics management without introducing a lot of complexity.

However, GlobalAlloc does not provide per-task memory management, which is essential for our use case. To address this, we found tokio::task_local.

tokio::task_local is a similar method to thread_local that is managed by the tokio runtime. The combination of GlobalAlloc and task_local provides a powerful and efficient solution for managing memory statistics. We can create a simple wrapper, TaskStatsAlloc, over any underlying allocator. It is safe, lightweight, and user-friendly.

The GlobalAlloc trait has four methods. For the sake of simplicity, we will only consider the alloc and dealloc methods here.

pub unsafe trait GlobalAlloc { unsafe fn alloc(&self, layout: Layout) -> *mut u8; unsafe fn dealloc(&self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: Layout); }

Intuitive implementation

The most straightforward idea is to record the allocation count of memory in task_local.

task_local! { static ALLOCATED: AtomicUsize; } pub struct TaskStatsAlloc<A>(A); unsafe impl<A: GlobalAlloc> GlobalAlloc for TaskStatsAlloc<A> { unsafe fn alloc(&self, layout: std::alloc::Layout) -> *mut u8 { let _ = ALLOCATED.try_with(|allocated| { allocated.fetch_add(layout.size(), std::sync::atomic::Ordering::Relaxed); }); self.0.alloc(layout) } unsafe fn dealloc(&self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: std::alloc::Layout) { let _ = ALLOCATED.try_with(|allocated| { allocated.fetch_sub(layout.size(), std::sync::atomic::Ordering::Relaxed); }); self.0.dealloc(ptr, layout) } }

And we can test the code with a simple program:

#[global_allocator] static GLOBAL: TaskStatsAlloc<System> = TaskStatsAlloc(System); #[tokio::main] async fn main() { let task1 = tokio::spawn(ALLOCATED.scope(0.into(), async { let _v = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]; ALLOCATED.with(|v| { println!("Allocated {}", v.load(std::sync::atomic::Ordering::Relaxed)); }); })); let task2 = tokio::spawn(ALLOCATED.scope(0.into(), async { let _v = vec![1, 2, 3]; ALLOCATED.with(|v| { println!("Allocated {}", v.load(std::sync::atomic::Ordering::Relaxed)); }); })); let _ = futures::join!(task1, task2); }

If you run the program on a 64-bit machine, you will get Allocated 24 and Allocated 12 in your output in any order.

However, something went wrong if you try to move memory between different scopes.

#[tokio::main] async fn main() { let (tx, rx) = oneshot::channel(); let task1 = tokio::spawn(ALLOCATED.scope(0.into(), async { let data = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]; tx.send(data) })); let task2 = tokio::spawn(ALLOCATED.scope(0.into(), async { { let _data = rx.await.unwrap(); } ALLOCATED.with(|v| { println!("Allocated {}", v.load(std::sync::atomic::Ordering::Relaxed)); }); })); let _ = futures::join!(task1, task2); }

There is an undefined behavior (UB) here, but it’s very likely that on your 64-bit machine, the output will be Allocated 18446744073709551512. Obviously, data was allocated in task1, moved to task2, and then deallocated in task2, causing task2 to destruct the 24 bytes it never allocated, resulting in an unsigned integer underflow.

Memory movement is one of the most important features of Rust, but it can lead to significant biases in our memory statistics. Many tasks may destruct memory from other tasks, leading to undercounted memory. Conversely, other tasks may have virtual inflated results due to the memory being moved.

Introduce scope meta

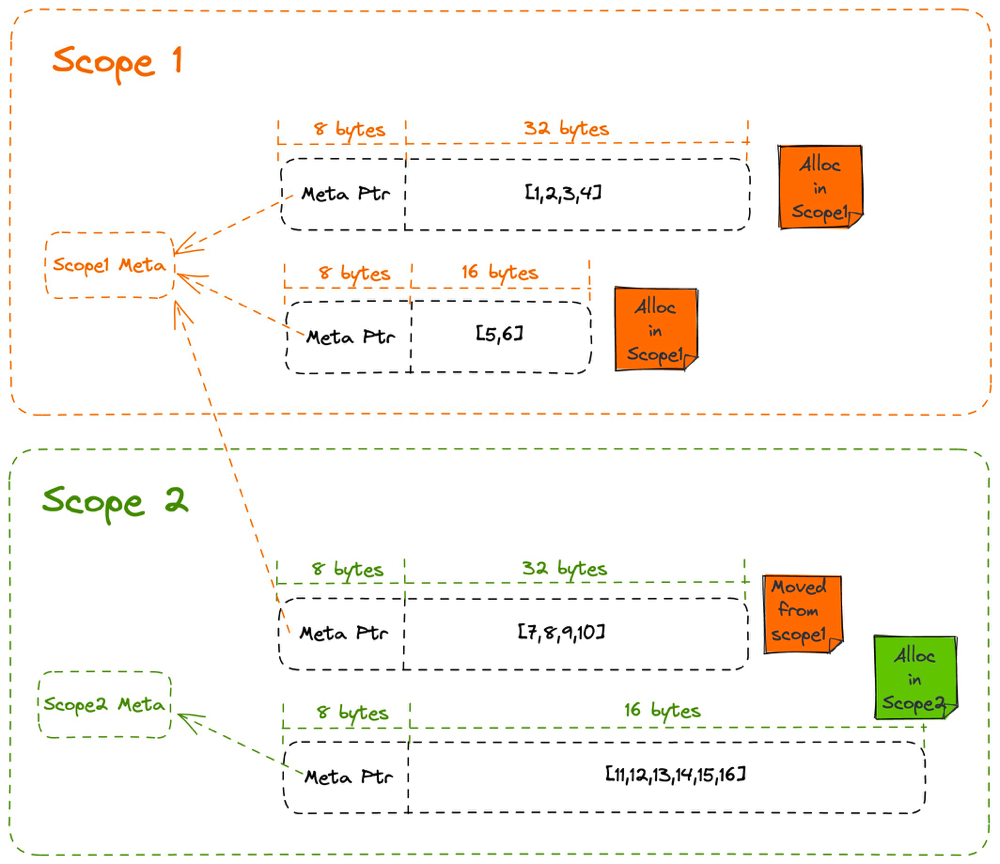

The core issue with the previous approach is that, memory movement effectively leaks the memory from its original scope statistics, but move itself is inevitable and cannot be hooked. Instead, we could take a classic approach: allocate a metadata block for each scope and add an extra pointer to the metadata block to every pointer, which is similar to a vtable. When we allocate memory, we record the metadata pointer of the current scope. When we deallocate memory, we operate on the scope that was allocated, rather than the current scope.

static GLOBAL_ALLOC: System = System; #[repr(transparent)] pub struct TaskLocalBytesAllocated(NonNull<AtomicUsize>); impl Default for TaskLocalBytesAllocated { fn default() -> Self { unsafe { TaskLocalBytesAllocated(NonNull::new_unchecked(Box::leak(Box::new( AtomicUsize::new(0), )))) } } } unsafe impl Send for TaskLocalBytesAllocated {} impl TaskLocalBytesAllocated { pub fn val(&self) -> usize { unsafe { self.0.as_ref().load(Ordering::Relaxed) } } } task_local! { pub static BYTES_ALLOCATED: TaskLocalBytesAllocated; } struct TaskLocalAlloc; unsafe impl GlobalAlloc for TaskLocalAlloc { unsafe fn alloc(&self, layout: std::alloc::Layout) -> *mut u8 { // Add extra 8 bytes at the layout header. let new_layout = Layout::from_size_align_unchecked(layout.size() + usize::BITS as usize, layout.align()); BYTES_ALLOCATED .try_with(|bytes| { // Add the allocation to scope statistics. bytes.0.as_ref().fetch_add(layout.size(), Ordering::Relaxed); // Allocate the layout from the original allocator. let ptr = GLOBAL_ALLOC.alloc(new_layout); // Assign scope meta address to the first 8 bytes. *(ptr as *mut usize) = bytes.0.as_ptr() as usize; // We should return the user the pointer with 8 bytes offset. let ptr = ptr.add(usize::BITS as usize); ptr }) .unwrap_or_else(|_| { let ptr = GLOBAL_ALLOC.alloc(new_layout); // If the allocation doesn't happen in any scope, // assign the meta scope ptr to 0. *(ptr as *mut usize) = 0; let ptr = ptr.add(usize::BITS as usize); ptr }) } unsafe fn dealloc(&self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: std::alloc::Layout) { // Calculate the new_layout using the same rule in `alloc`. let new_layout = Layout::from_size_align_unchecked(layout.size() + usize::BITS as usize, layout.align()); // Get the meta scope ptr. let ptr = ptr.sub(usize::BITS as usize); let bytes = (*(ptr as *const usize)) as *const AtomicUsize; if let Some(bytes) = bytes.as_ref() { // Subtract the allocation from scope statistics. bytes.fetch_sub(layout.size(), Ordering::Relaxed); } GLOBAL_ALLOC.dealloc(ptr, new_layout) }

In this implementation, we allocate a TaskLocalBytesAllocated for each tokio task scope (See TaskLocalBytesAllocated::default. This is a wrapper around an *AtomicUsize that records the amount of memory allocated by that particular scope. Since the address of this allocation is saved within the pointers that are allocated in this scope, deallocation will still decrement the corresponding TaskLocalBytesAllocated.

Fix the memory leak in TaskLocalBytesAllocated

We have noticed that when creating TaskLocalBytesAllocated, we use Box::leak to create the AtomicUsize metadata, but we never deallocate it. This can lead to an 8-byte memory leak for each scope. This unlimited leakage is unacceptable for programs that continuously create new task scopes.

However, we cannot reclaim this metadata when the scope exits because the memory allocated by this scope may be referenced by other scopes or global variables. If we were to recycle this metadata at this point, it would result in a dangling pointer, and accessing a dangling pointer during deallocation is undefined behavior (UB).

The current situation is similar to the one that can be managed by Arc. Indeed, we can use Arc to easily solve it. However, since this approach has critical performance requirements, we can employ some clever techniques to deal with the issue.

The lifecycle of TaskLocalBytesAllocated has two stages, which are marked by the exit of the scope. In the first stage, the scope allocates and deallocates memory. In the second stage, since the scope has completely exited, no new allocation will occur, and only the remaining memory will be freed. Therefore, the end of the second lifecycle is indicated by the TaskLocalBytesAllocated value dropping to 0 after the scope has exited.

To simplify implementation, we can create a 1-byte guard at the beginning of the scope and release it when the scope exits. This ensures that the value is never 0 in the first stage. As a result, when the value drops to 0, the metadata itself also needs to be reclaimed. This is equivalent to a thin Arc where the value is also the reference count. In this case, only one atomic variable needs protection. Therefore, Relaxed Order can be used without adding an Acquire/Release fence, unlike Arc.

#[repr(transparent)] #[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug)] pub struct TaskLocalBytesAllocated(Option<&'static AtomicUsize>); impl Default for TaskLocalBytesAllocated { fn default() -> Self { Self(Some(Box::leak(Box::new_in(0.into(), System)))) } } impl TaskLocalBytesAllocated { pub fn new() -> Self { Self::default() } /// Create an invalid counter. pub const fn invalid() -> Self { Self(None) } /// Adds to the current counter. #[inline(always)] fn add(&self, val: usize) { if let Some(bytes) = self.0 { bytes.fetch_add(val, Ordering::Relaxed); } } /// Adds to the current counter without validity check. /// /// # Safety /// The caller must ensure that `self` is valid. #[inline(always)] unsafe fn add_unchecked(&self, val: usize) { self.0.unwrap_unchecked().fetch_add(val, Ordering::Relaxed); } /// Subtracts from the counter value, and `drop` the counter while the count reaches zero. #[inline(always)] fn sub(&self, val: usize) { if let Some(bytes) = self.0 { // Use `Relaxed` order as we don't need to sync read/write with other memory addresses. // Accesses to the counter itself are serialized by atomic operations. let old_bytes = bytes.fetch_sub(val, Ordering::Relaxed); // If the counter reaches zero, delete the counter. Note that we've ensured there's no // zero deltas in `wrap_layout`, so there'll be no more uses of the counter. if old_bytes == val { // No fence here, this is different from ref counter impl in https://www.boost.org/doc/libs/1_55_0/doc/html/atomic/usage_examples.html#boost_atomic.usage_examples.example_reference_counters. // As here, T is the exactly Counter and they have same memory address, so there // should not happen out-of-order commit. unsafe { Box::from_raw_in(bytes.as_mut_ptr(), System) }; } } } #[inline(always)] pub fn val(&self) -> usize { self.0 .as_ref() .expect("bytes is invalid") .load(Ordering::Relaxed) } }

And dealloc just call subdirectly.

unsafe fn dealloc(&self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: Layout) { let new_layout = Layout::from_size_align_unchecked(layout.size() + usize::BITS as usize, layout.align()); // Get the meta scope ptr. let ptr = ptr.sub(usize::BITS as usize); let bytes: TaskLocalBytesAllocated = *ptr.cast(); bytes.sub(layout.size()); GLOBAL_ALLOC.dealloc(ptr, wrapped_layout); }

We also create a simple wrapper for caller to create the guard and monitor the metrics value:

pub async fn allocation_stat<Fut, T, F>(future: Fut, interval: Duration, mut report: F) -> T where Fut: Future<Output = T>, F: FnMut(usize), { BYTES_ALLOCATED .scope(TaskLocalBytesAllocated::new(), async move { // The guard has the same lifetime as the counter so that the counter will keep positive // in the whole scope. When the scope exits, the guard is released, so the counter can // reach zero eventually and then `drop` itself. let _guard = Box::new(1); let monitor = async move { let mut interval = tokio::time::interval(interval); loop { interval.tick().await; BYTES_ALLOCATED.with(|bytes| report(bytes.val())); } }; let output = tokio::select! { biased; _ = monitor => unreachable!(), output = future => output, }; output }) .await }

Pros and Cons

This implementation still has many drawbacks:

- Memory overhead: Small objects on the heap usually have a size of about 60-70 bytes, and allocating an additional 8 bytes of metadata incurs a non-negligible cost.

- Atomic instruction overhead: Although we have optimized to a simple RELAXED atomic instruction, there is still a certain performance cost due to the critical path. There is room for further optimization, such as separately counting the current task and other tasks for the total value, and modifying the current task value without using atomic instructions.

- Long-lived memory: Some allocated memory may live for a long time, which will also prevent the associated task metadata from being reclaimed, such as creating a connection in a task and moving it to the connection pool. However, long-lived memory is usually bounded, so adding an additional 8 bytes is acceptable. This can also cause some statistical errors.

However, the benefits are also very obvious. This implementation has zero invasion on the application code, and all complexity is covered in the allocator.

Further plan

I have tested this approach in our application and it performed well. We were able to obtain detailed memory statistics for each module or query without significantly impacting the speed of the application. The impact was approximately 10% in high-concurrent workloads, such as sysbench, and almost no influence for long-running workloads.

The current implementation has not been published on crates.io so far, as I am contemplating the manner in which statistical values monitoring can be presented to the user in a more convenient way. At the same time, I am also exploring whether there are better ways to address some of the drawbacks mentioned above.