This is the second article on pr-demystifying topics. Each article labeled pr-demystifying will attempt to demystify the details behind the PR.

In this article, I’ll share my experience of making my first contribution (#74024) to rust by optimizing the best-case complexity of the slice::binary_search_by() function to O(1). Despite the fact that this optimization was already included in Rust 1.52, which was released on May 6, 2021, I believe it’s worth revisiting and shedding light on what went into making this improvement. Interestingly, this PR turned out to have a surprising connection with the Polkadot network downtime that occurred on May 24, 2021, half a month after Rust 1.52 has been released. If you’re curious to learn more, keep reading.

slice::binary_search_by

The slice::binary_search_by() method is a simple function that performs a binary search to find the target value seek in a given ordered slice.

let s = [0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55]; let seek = 13; assert_eq!(s.binary_search_by(|probe| probe.cmp(&seek)), Ok(9)); let seek = 4; assert_eq!(s.binary_search_by(|probe| probe.cmp(&seek)), Err(7)); let seek = 100; assert_eq!(s.binary_search_by(|probe| probe.cmp(&seek)), Err(13)); let seek = 1; let r = s.binary_search_by(|probe| probe.cmp(&seek)); assert!(match r { Ok(1..=4) => true, _ => false, });

If the target value is found, the method returns Ok(pos), where pos is the position of the target value in the slice. If not found, the method returns Err(pos), where pos is the position where the target value can be inserted to maintain the order of the slice. The other slice::binary_search() and slice::binary_search_by_key() methods all use slice::binary_search_by() internally.

Before the optimization in Rust 1.52, there was a small issue with the implementation of slice::binary_search_by(). If there were multiple consecutive target values in the slice, it would always find the last one before returning. This meant that the best-case time complexity was O(log n) instead of O(1). In other words, the function would return immediately if the target value was found.

Here is the code before 1.52:

#[inline] pub fn binary_search_by<'a, F>(&'a self, mut f: F) -> Result<usize, usize> where F: FnMut(&'a T) -> Ordering, { let s = self; let mut size = s.len(); if size == 0 { return Err(0); } let mut base = 0usize; while size > 1 { let half = size / 2; let mid = base + half; // SAFETY: the call is made safe by the following inconstants: // - `mid >= 0`: by definition // - `mid < size`: `mid = size / 2 + size / 4 + size / 8 ...` let cmp = f(unsafe { s.get_unchecked(mid) }); base = if cmp == Greater { base } else { mid }; size -= half; } // SAFETY: base is always in [0, size) because base <= mid. let cmp = f(unsafe { s.get_unchecked(base) }); if cmp == Equal { Ok(base) } else { Err(base + (cmp == Less) as usize) } }

Optimization(1)

Yeah, this is what I found when I looking the source code of slice::binary_search_by(), I believe we should improve it. So I submit my first PR to Rust on July 4, 2020. Can we judge cmp == Equal in the while loop? If they are equal, return Ok directly, otherwise continue to search for binary divisions.

while size > 1 { let half = size / 2; let mid = base + half; // SAFETY: // mid is always in [0, size), that means mid is >= 0 and < size. // mid >= 0: by definition // mid < size: mid = size / 2 + size / 4 + size / 8 ... let cmp = f(unsafe { s.get_unchecked(mid) }); if cmp == Equal { return Ok(base); } else if cmp == Less { base = mid }; size -= half; }

For the sake of brevity, repeated code will be omitted.

Well, it seems logically correct, the unit tests also passed, we will call it optimization(1). Within a few days, @dtolnay reviewed my PR and replied: Would you be able to put together a benchmark assessing the worst case impact? The new implementation does potentially 50% more conditional branches in the hot loop.

Ok, let’s do a benchmark:

// before improvement(1) test slice::binary_search_l1 ... bench: 59 ns/iter (+/- 4) test slice::binary_search_l1_with_dups ... bench: 59 ns/iter (+/- 3) test slice::binary_search_l2 ... bench: 76 ns/iter (+/- 5) test slice::binary_search_l2_with_dups ... bench: 77 ns/iter (+/- 17) test slice::binary_search_l3 ... bench: 183 ns/iter (+/- 23) test slice::binary_search_l3_with_dups ... bench: 185 ns/iter (+/- 19)

// after improvement(1) test slice::binary_search_l1 ... bench: 58 ns/iter (+/- 2) test slice::binary_search_l1_with_dups ... bench: 37 ns/iter (+/- 4) test slice::binary_search_l2 ... bench: 76 ns/iter (+/- 3) test slice::binary_search_l2_with_dups ... bench: 57 ns/iter (+/- 6) test slice::binary_search_l3 ... bench: 200 ns/iter (+/- 30) test slice::binary_search_l3_with_dups ... bench: 157 ns/iter (+/- 6)

Based on benchmark data, it is evident that the new implementation showed significant improvements in the with_dups mode, where there are more repeated elements. However, the normal mode’s performance at the l3 level is much worse than the previous version. The possible reason behind this could be the 50% increase in conditional branches in the hot loop, as pointed out by @dtolnay. To understand the significance of conditional branches in the hot loop, we need to delve into the concept of branch prediction.

Branch prediction

Branch prediction is a technique used by modern CPUs to predict the next possible branch in advance when encountering a branch in order to speed up the parallelization of instructions. A dedicated branch predictor is typically built into the CPU to support this functionality.

For more information on branch prediction and how it affects performance, we recommend reading Stackoverflow’s answer to “Why is processing a sorted array faster than processing an unsorted array?” This answer provides a clear explanation of branch prediction and its impact on performance.

Branch

Before delving into branch prediction, it’s important to understand what a branch is. At the high-level programming language, branches are statements such as if/else/else if, goto, or switch/match. However, these statements are ultimately converted into jump instructions in assembly code. In x86 assembly, jump instructions start with j and include:

| instruction | effect |

|---|---|

| jmp | Always jump |

| je | Jump if cmp is equal |

| jne | Jump if cmp is not equal |

| jg | Signed > (greater) |

| jge | Signed >= |

| jl | Signed < (less than) |

| jle | Signed <= |

| ja | Unsigned > (above) |

| jae | Unsigned >= |

| jb | Unsigned < (below) |

| jbe | Unsigned <= |

| jecxz | Jump if ecx is 0 |

| jc | Jump if carry: used for unsigned overflow, or multiprecision add |

| jo | Jump if there was signed overflow |

To illustrate, we can write a Rust program that uses if/else statements, and look at the corresponding assembly code. For example:

#![allow(unused_assignments)] pub fn main() { let mut a: usize = std::env::args().nth(1).unwrap().parse().unwrap_or_defaul(); if a > 42 { a = 1; } else { a = 0; } }

Here’s the relevant portion of the resulting assembly code:

.LBB99_7: cmp qword ptr [rsp + 56], 42 ; if a > 42 jbe .LBB99_10 mov qword ptr [rsp + 56], 1 ; a = 1 jmp .LBB99_11 .LBB99_10: mov qword ptr [rsp + 56], 0 ; a = 0 .LBB99_11: add rsp, 200 ret

Here, the cmp instruction compares the value in register a to the value 42, and the jbe instruction decides whether to jump to the .LBB99_10 label or not. If the jump is taken, the instruction at .LBB99_10 is executed, which sets a to 0. If not, the instruction continue to execute, which sets a to 1.

Now that we understand what branches are, we can discuss why the CPU needs to predict branches, which leads us to the next topic: instruction pipelines.

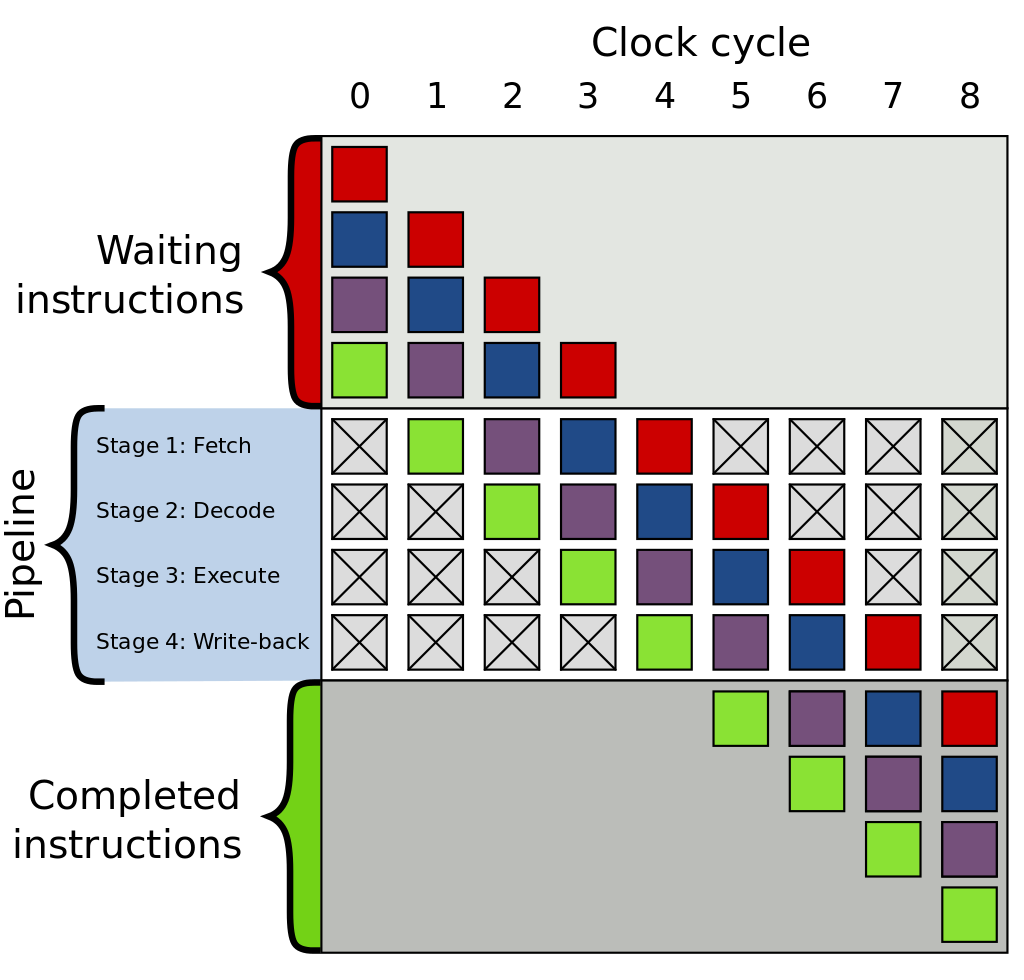

Instruction pipelining

Instruction pipeline is a technique used in modern processors to increase instruction throughput by overlapping the execution of multiple instructions. This technology began in earnest in the late 1970s.

The CPU generally processes an instruction in several stages:

- Instruction Fetch

- Instruction Decode

- Execute

- Register write back

This is similar to a factory producing an item that requires multiple processes. Imagine how slow a factory would be if it were to produce the first item in its entirety each time before moving on to produce the next item. So, similar to the industrial assembly line of the 19th century, CPUs can break down the instruction execution process into different stages and execute them in parallel. When the first instruction enters the decode stage, the second instruction can enter the fetch stage without waiting for the first instruction to complete all stages.

This picture from Wikipedia can help you understand.

However, this can cause issues when a conditional branch instruction is encountered, which can change the flow of execution and invalidate the instructions already in the pipeline. This leads us to the next topic: branch prediction.

Why Branch Prediction is Important

The instruction pipeline executes instructions like a factory assembly line, including the jump instruction mentioned earlier. However, a problem with the jump instruction is that the CPU needs to know whether to jump or not in the next clock cycle, and this can only be determined after the preceding logic has been executed. In the example given earlier, the jump instruction can decide whether to jump to the .LBB99_10 part or not only after the cmp judgment is completed. However, the CPU’s instruction pipeline cannot wait, as doing so would waste a clock cycle. To avoid this problem, branch prediction was invented.

The CPU’s branch predictor predicts in advance which branch the jump instruction will jump to, and then puts the predicted branch into the pipeline for execution. If the prediction is correct, the CPU can continue to execute the subsequent instructions. However, if the prediction fails (branch misprediction), the CPU must discard the result of the branch just executed and switch to the correct branch again. While too many prediction failures can affect performance, branch prediction is an essential technique for improving processor performance. Over the years, CPU branch predictors have become more advanced, and people continue to use various methods to improve the accuracy of branch prediction.

Avoid branch predictions in hot loop

Although modern CPUs have advanced branch predictors, it is still important to avoid branch predictions at the software level, especially in hot loops. One common optimization is to use branchless code and avoid writing if/else statements in loops. There are many examples of branchless code in the standard library that are designed to optimize performance, such as the count() method of std::iter::Filter.

pub struct Filter<I, P> { iter: I, predicate: P, } impl<I: Iterator, P> Iterator for Filter<I, P> where P: FnMut(&I::Item) -> bool, { type Item = I::Item; // this special case allows the compiler to make `.filter(_).count()` // branchless. Barring perfect branch prediction (which is unattainable in // the general case), this will be much faster in >90% of cases (containing // virtually all real workloads) and only a tiny bit slower in the rest. // // Having this specialization thus allows us to write `.filter(p).count()` // where we would otherwise write `.map(|x| p(x) as usize).sum()`, which is // less readable and also less backwards-compatible to Rust before 1.10. // // Using the branchless version will also simplify the LLVM byte code, thus // leaving more budget for LLVM optimizations. #[inline] fn count(self) -> usize { #[inline] fn to_usize<T>(mut predicate: impl FnMut(&T) -> bool) -> impl FnMut(T) -> usize { move |x| predicate(&x) as usize } self.iter.map(to_usize(self.predicate)).sum() } }

The Filter type of the standard library overrides the count() method when implementing Iterator.

If we were not aware of the problem of branch prediction, we might implement it like this:

// Bad #[inline] fn count(self) -> usize { let sum = 0; self.iter.for_each(|x| { if self.predicate(x) { sum += 1; } }); sum }

However, this implementation has an if statement in the loop, which causes the CPU to perform a large number of branch predictions, and these branch predictions are almost random. This makes it difficult for the CPU to improve its prediction accuracy based on history, resulting in lower performance. Instead, the implementation of the standard library is completely branchless, which not only has much better performance but also makes it easier for LLVM to do more optimizations.

Notice:

Writing good branchless code to optimize performance is an important topic, and there is plenty of information available on the web on how to do so. However, it’s worth noting that branchless code can sacrifice code readability and should be used judiciously.

Comparison

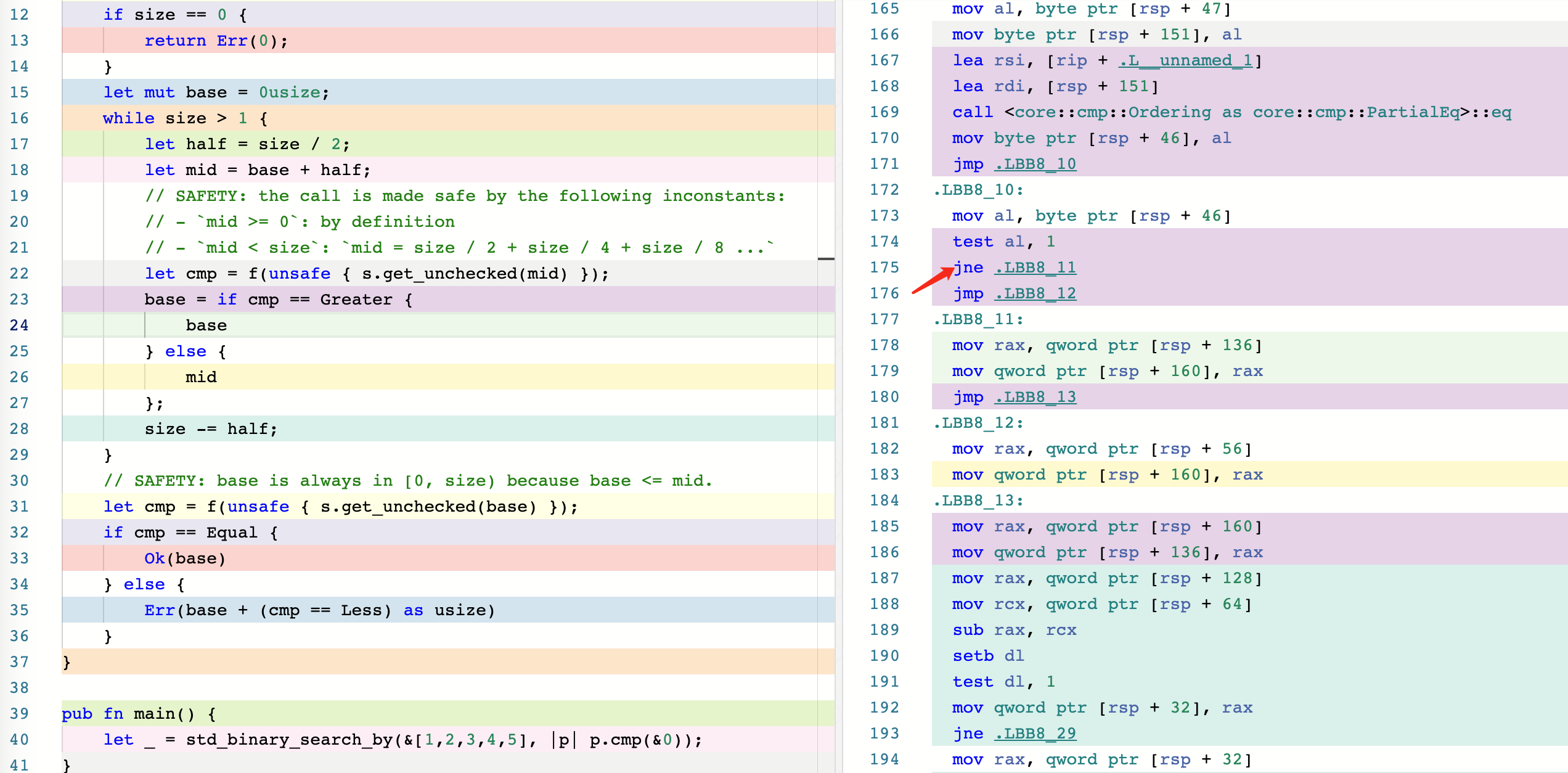

As we mentioned earlier, our new implementation of slice::binary_search_by() may be slower than the original version of the standard library in some cases. This can be attributed to the additional branch that our code requires.

To help you compare the two versions, we’ve included screenshots of their corresponding assembly code, available at this Godbolt link: https://rust.godbolt.org/z/8dGbY8Pe1. As you can see, the new version includes an extra jne instruction, which adds another branch that the CPU has to predict.

Note that the

jmpinstruction is a direct jump and does not require branch prediction.

- Before optimization(1)

- After optimization(1)

It’s possible that the original authors of slice::binary_search_by() did not prioritize achieving the best time complexity of O(1) because they wanted to avoid redundant branch prediction. This is because an early return cannot be achieved without branching, and avoiding branches can help reduce the number of branch predictions made by the CPU.

Optimization(2)

In our pursuit of optimization, we must go further. Thanks to @tesuji, who provided a repo tesuji/rust-bench-binsearch to benchmark the performance of current Rust slice::binary_search (v1.46.0) and their implementations. It turns out that @tesuji’s version is faster in most cases and also more readable than the standard library version, despite introducing an extra branch.

From the PR comment.

I guess the new implementation let CPU guessing branch more precisely. Related info could be found in #53823.

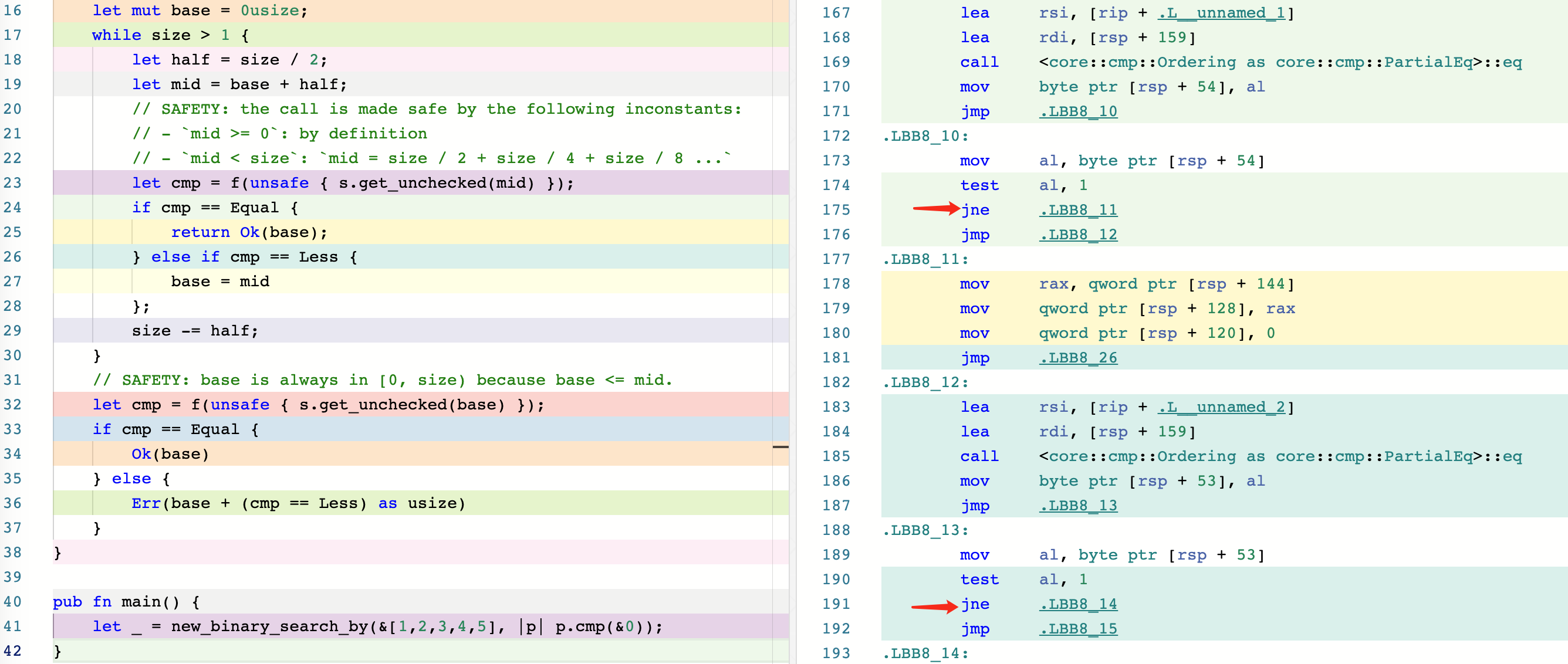

Here is @tesuji’s new version, which we will call optimization(2):

pub fn binary_search_by<'a, F>(&'a self, mut f: F) -> Result<usize, usize> where F: FnMut(&'a T) -> Ordering, { let mut left = 0; let mut right = self.len(); while left < right { // never overflow because `slice::len()` max is `isize::MAX`. let mid = (left + right) / 2; // SAFETY: the call is made safe by the following invariants: // - `mid >= 0` // - `mid < size`: `mid` is limited by `[left; right)` bound. let cmp = f(unsafe { self.get_unchecked(mid) }); if cmp == Less { left = mid + 1; } else if cmp == Greater { right = mid; } else { return Ok(mid); } } Err(left) }

Let’s take a look at its generated assembly code.

It can be seen that there are still two jne instructions, so the performance in non-with_dups mode may not be as high as that of the standard library. However, it is much better than the performance of optimization(1).

A few days later @m-ou-se from the libs team replied with a comment. She also benchmarked and found that primitive types like u32 with l1 level data are still slower than the standard library. However, for types that require more time to compare (like String), the new implementation outperforms the standard library implementation in all cases.

From the PR comment

Important to note here is that almost all benchmarks on this page are about slices of usizes. Slices of types that take more time to compare (e.g. [String]) seem faster with this new implementation in all cases.

After much discussion, @m-ou-se decided to run a crater test to see if the PR has a significant impact on all crates on crates.io. In the end, the Rust library team agreed to merge this PR.

From the PR comment

We discussed this PR in a recent library team meeting, in which we agreed that the proposed behaviour (stopping on Equal) is preferrable over optimal efficiency in some specific niche cases. Especially considering how small most of the differences are in the benchmarks above.

From the PR comment

The breakage in the crater report looks reasonably small. Also, now that partition_point is getting stabilized, there’s a good alternative for those who want the old behaviour of binary_search_by. So we should go ahead and start on getting this merged. :)

Integer overflow

However, scottmcm pointed out another problem:

// never overflow because `slice::len()` max is `isize::MAX`. let mid = (left + right) / 2;

This line of code may overflow under Zero Sized Type (ZST) ! Let’s analyze why.

The return value of slice::len() is the usize, but for non-zero size types (non-ZST), the maximum value of slice::len() can only be isize::MAX. Therefore, as written in the comment, (isize::MAX + isize::MAX) / 2 will not exceed usize::MAX, and there will be no overflow. However, if all the elements in the slice are zero-sized (such as () ), then the length of the slice can reach usize::MAX. Although in the case of [(); usize::MAX].binary_search(&()), we will find the result in O(1) and return it immediately, but if we write b.binary_search_by(|_| Ordering::Less), it causes an integer overflow.

Why the maximum length of non-ZST slice is isize?

The simplest reason is that we cannot construct an array or slice with all elements non-ZST and the length of usize::MAX, which would not compile. For example, even taking the simplest type of bool that only occupies 1 byte, the size of [bool; usize::MAX] will be equal to std::mem::size_of::<bool>() * usize::MAX, which is a huge number, and the memory of ordinary computers is simply not enough.

fn main() { assert_eq!(std::mem::size_of::<bool>(), 1); // error: values of the type `[bool; 18446744073709551615]` are too big // for the current architecture let _s = [true; usize::MAX]; }

But it is possible for ZSTs because std::mem::size_of::<()>() * usize::MAX is still zero.

fn main() { assert_eq!(std::mem::size_of::<()>(), 0); let s = [(); usize::MAX]; assert_eq!(s.len(), usize::MAX); }

However, the above explanation is still not rigorous enough, such as std::mem::size_of::<bool>() * isize::MAX is still a big number. Why is isize::MAX ok? The fundamental reason is that the maximum offset of Rust pointer addressing only allows isize::MAX. See the documentation of std::pointer::offset() and std::slice::from_raw_parts() to learn more. For the ZST type, the compiler will optimize it, and does not need addressing at all, so the maximum size can be usize::MAX.

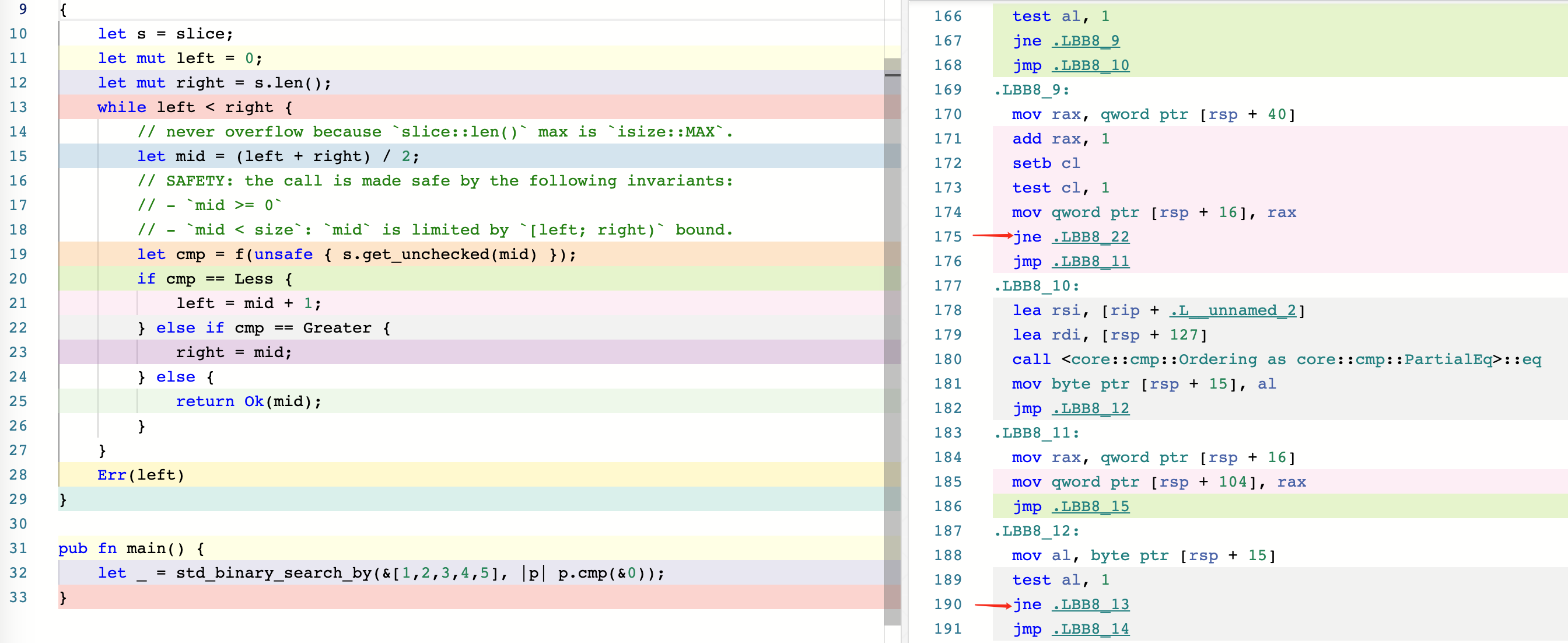

The final version

After realizing the problem of integer overflow, the solution was relatively simple. This was my submission at the time, and I also added a unit test against overflow.

pub fn binary_search_by<'a, F>(&'a self, mut f: F) -> Result<usize, usize> where F: FnMut(&'a T) -> Ordering, { let mut size = self.len(); let mut left = 0; let mut right = size; while left < right { let mid = left + size / 2; // SAFETY: the call is made safe by the following invariants: // - `mid >= 0` // - `mid < size`: `mid` is limited by `[left; right)` bound. let cmp = f(unsafe { self.get_unchecked(mid) }); // The reason why we use if/else control flow rather than match // is because match reorders comparison operations, which is // perf sensitive. // This is x86 asm for u8: https://rust.godbolt.org/z/8Y8Pra. if cmp == Less { left = mid + 1; } else if cmp == Greater { right = mid; } else { return Ok(mid); } size = right - left; } Err(left) } #[test] fn test_binary_search_by_overflow() { let b = [(); usize::MAX]; assert_eq!(b.binary_search_by(|_| Ordering::Equal), Ok(usize::MAX / 2)); assert_eq!(b.binary_search_by(|_| Ordering::Greater), Err(0)); assert_eq!(b.binary_search_by(|_| Ordering::Less), Err(usize::MAX)); }

It’s best to avoid using the let mid = (left + right) / 2 code, which can be prone to integer overflow, and instead use let mid = left + size / 2 to to prevent overflow.

We also received a question about why we used if/else instead of match. We investigated this by examining the assembly code generated by both versions and found that the match version had more instructions and a different order of cmp instructions, resulting in lower performance. Even after almost two years of this pull request being merged, another pull request (#106969) attempted to replace if with match in the binary search function, but it couldn’t be merged due to regression.

The story after this PR merged

Polkadot’s network downtime

This PR has an interesting connection to the Polkadot network downtime that occurred on May 24, 2021, half a month after Rust 1.52 was released.

It is important to note that this PR was not responsible for the network downtime. The culprit was an out-of-memory (OOM) error, as detailed in the Polkadot postmortem report. The network recovered after an hour and ten minutes of downtime by fixing the OOM. However, this PR did cause another error, where several nodes failed with a “storage root mismatch” error, as they were using a different Rust compiler version before and after the fix. One version was prior to Rust 1.52, which did not have the optimization from this PR, and the other was after 1.52, with the optimization.

The reason for this error was that the Polkadot team relied on the returned position of slice::binary_search_by() deterministically, despite the docs stating that “if there are multiple matches, then any one of the matches could be returned”. Prior to Rust 1.52, binary_search_by() always returned the last one if multiple matches are found. After this optimization, it no longer always returns the last one. Here is a demonstration:

let mut s = vec![0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55]; let num = 1; let idx = s.binary_search(&num); // Prior to Rust 1.52 assert_eq!(idx, 4); // After Rust 1.52 assert_eq!(idx, 3);

Deterministic v.s Non-deterministic

In computer science, a deterministic algorithm is an algorithm that always produces the same output given the same input. This means that if the same input is provided to the algorithm multiple times, it will always produce the same result. This is important for many applications, as it allows for reliable and predictable behavior. Binary search is a classic example of a deterministic algorithm. While the non-deterministic algorithm is an algorithm that, even for the same input, can exhibit different behaviors on different runs, as opposed to a deterministic algorithm.

In other words, slice::binary_search_by() is deterministic in the same Rust version, however, it does not guarantee to be deterministic across Rust versions. That’s why the PR (#85985) clarified the documentation.

The docs of slice::binary_search_by()

If there are multiple matches, then any one of the matches could be returned. The index is chosen deterministically, but is subject to change in future versions of Rust.

Another important method to mention is slice::partition_point(), which also uses binary_search_by() underneath but is deterministic in nature. The choice between binary_search_by() and partition_point() depends on your specific use case.

pub fn partition_point<P>(&self, mut pred: P) -> usize where P: FnMut(&T) -> bool, { self.binary_search_by(|x| if pred(x) { Less } else { Greater }).unwrap_or_else(|i| i) }

Hyrum’s Law: It’s Murphy’s Law for APIs

The Polkadot network accident is a real-life example of Hyrum’s Law in practice. Named after Google software engineer Hyrum Wright, Hyrum’s Law states that as the number of users of an API increases, so does the likelihood that someone will depend on any behavior of the system, even those that are not explicitly documented or guaranteed by the API contract. This can lead to unintended consequences and compatibility issues when changes are made to the API or underlying system. Here is what Hyrum’s law says:

With a sufficient number of users of an API, it does not matter what you promise in the contract: all observable behaviors of your system will be depended on by somebody.

In our example, deterministically depending on a non-deterministic API inevitably falls prey to Hyrum’s Law, no matter how much we improve the documentation or how rigorously we test it, such as using crater in this PR.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have delved into the intricacies of optimizing Rust’s binary search algorithm, discussing how we managed to achieve a best-case performance of O(1) while avoiding branch prediction in the hot loop. Additionally, we explored the aftermath of the PR, including the Polkadot network downtime and the application of Hyrum’s Law. This article is the second installment in the #pr-demystifying series, and we hope that it has inspired more people to share their PR stories. Thank you for reading, and if you have any questions, please feel free to leave a comment below.